Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

A Malaria-Free World

What once seemed like a pipe dream—the global elimination of malaria—may now be possible, with the right focus.

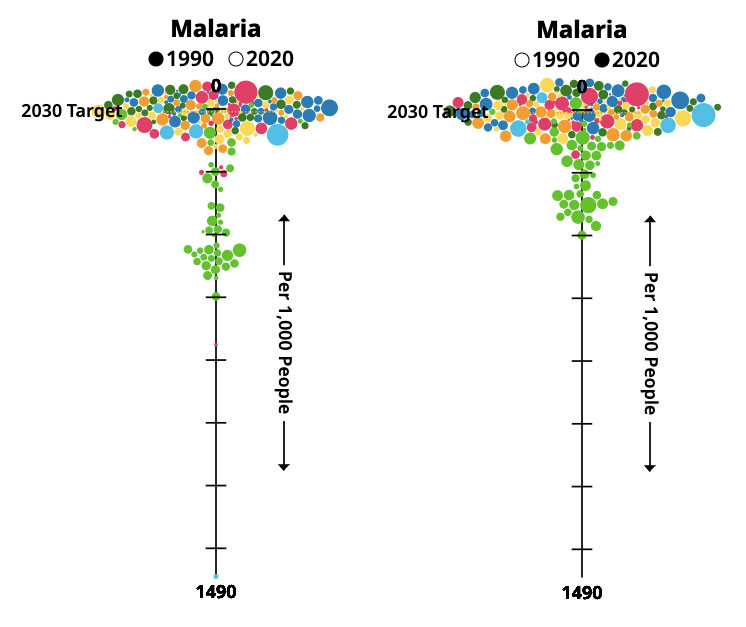

From one perspective, the global fight against malaria has been waged remarkably well. The World Health Organization’s (WHO) 2020 report on malaria estimated that in 2000, 736,000 people worldwide died from the disease; in 2019, the number had shrunk to 453,000. In those 19 years, the organization estimates that malaria prevention and treatment efforts averted 7.6 million deaths. In Africa, where the vast majority of malaria cases are concentrated and amidst a rapidly growing population, malaria incidence per 1000 people decreased from 363 to 225 in the same period.

But from another perspective, the results are disappointing. The malaria reduction targets set for 2030 and 2040 will likely not be met. The Covid-19 pandemic threw an additional, enormous hurdle into the mix. Although the WHO’s initial, dire forecasts—that the pandemic would set back progress on malaria a decade—did not come true, Covid’s full effect has yet to be seen.

Below we speak with Alan Court, Senior Advisor at the Office of the WHO Ambassador for Global Strategy and Health Financing. The conversation is an up-to-date overview of all the moving pieces behind the push to eliminate malaria: innovations in medicines and vaccines, plus what needs to happen to live in a malaria-free world and how quickly we might get there. Unsaid but underpinning the discussion was that what once seemed like a pipe dream may now be possible. With the right focus, the pertinent question around elimination could be not if, but when.

Since 2000 there has been strong progress against malaria. China made the news recently when it was declared malaria-free by the World Health Organization (WHO), joining 39 other nations with that status. What brought us here?

Alan Court: “Focus” is a single-word answer. A focus not only on controlling the disease, but also on trying to get rid of it. Initially it was about control—roll it back and we can live with it in smaller amounts. But it was understood a number of years ago that if you don’t eliminate it, it will come back. It’s a parasite, a biological animal, and it will adapt. And so will a mosquito. So there has been a greater focus on elimination, bringing down the quantity of malaria that there is in certain countries to manageable levels and then stamping it out.

China, as you mentioned, was certified malaria-free this year, which means it has been a number of years without indigenous cases. They might’ve had imported cases, but they haven’t transmitted indigenously within China. There’s also El Salvador, which after having very few cases for many years, for the previous three years has had no cases. That is fantastic, and that is the result of a deliberate attempt to focus on the region to eliminate malaria, spearheaded by several organizations along with the governments of Central America. El Salvador was the first of those to actually declare itself free. As I said, they were at a very low caseload before, but they did focus, and that focus helps them build up to deal with other things that might even be more pressing, like dengue fever.

It’s a virtuous cycle, in other words. Now the rate of progress against malaria is starting to slow down. Is that a simple case of we hit the low hanging fruit, and what’s ahead is a harder or more complicated process? Or is it a lack of focus or something else? I think what you said: it’s natural. The beginning of a plateau would be there since the low hanging fruits have been dealt with. For instance, insecticidal net distribution is most successful in the surroundings of towns and cities. In rural areas, it’s probably less successful the further out you go. So you do get that geographical issue of the harder-to-reach places are simply harder to reach.

How does one reach them, then? And if one wants to stamp out the disease, are there other ways? This is where we’re always looking at new or adapted technologies. Insecticidal nets, for instance, in many places are beginning to be less effective. They used to kill the mosquito that touched them; now maybe they only scare it away. Now we need nets that have two insecticides on them. All of this is being tried, and successfully, with new nets and new insecticides. Of course, they’re more expensive than the older ones, which have become very cheap. Their cheapness is both the advantage and the disadvantage of technology. The advantage of the cheapness is that you can buy a lot more of them and therefore distribute them further. The disadvantage is that they might not last as long, or be as effective, as the new nets, which are more expensive. It’s a trade-off.

Can we expect that those new nets will come down in price as the technology becomes more integrated? I’m sure as volumes of sales for the company increases, the prices will definitely come down. There’s no question about that.

There has been a lot of news about a potential malaria vaccine recently. Should we expect an efficacious one soon? Is it something you have your eye on, or is it beside the point? It’s not beside the point. Vaccines are desirable. We haven’t yet had a successful vaccine in the world that works against a parasite, and this is a parasite, not a bacteria or virus or fungus. That’s an issue.

There is new technology. It took over 30 years for the vaccine that is now in stage-four trials in a number of countries in Africa to get there. It’s safe, and it is effective up to a point, between 30 and 40% in field conditions. Therefore it would not replace anything. It would be one of the tools, because you don’t know where it’s going to be effective and where it isn’t.

That creates a problem for those handling the financing for this. The trials need to go ahead, and then a conclusion needs to be made. Where’s the best place to use the vaccine? Is it where there is a high parasite load or a low one? Does it help eliminate the disease or not? The vaccine doesn’t necessarily block transmission. It reduces the severity of the malaria. So it’s not a magic bullet.

The other vaccines coming behind potentially offer greater protection, but they are still many years out.

Which ones are those? There are some already in trials from two other companies. One is a whole sporozoite vaccine that has been trialed in Equatorial Guinea and in Tanzania, and now in other countries. The other one, out of Oxford, is also based on the whole sporozoite and is in trials in Africa. All of these offer solutions, but whether any of them will offer the complete solution remains to be seen when they get to the Phase Three trials and then go for final regulatory approval. But these ones coming up behind are actually doing better in the initial stages than that first one did in its initial stage. Therefore it’s possible they’ll provide better solutions or solutions for different areas. We don’t know yet; this is still where the question marks are. But there is hope, absolutely.

It’s funny to see a benefit in Covid, but because of the rapidity of adopting a technology to produce Covid vaccines, there’s the possibility of adapting it for other diseases as well. That lays out a lot of hope, too. Obviously it would be clearest for other viruses, possibly for other bacterias, but it would be great if it potentially could be useful for parasitic diseases.

What else is in motion to help end malaria? There are a lot of drugs and medicines—11 medicines have been approved in the last 20 years that are active and effective. Most of them are based on Artemisinin, which took over from Quinine-based medicines as they became less effective. The important thing is, those have to constantly adapt as well, because we are beginning to see a slow-down in the effectiveness of Artemisinin-based medicine. The fear is if it takes four days to clear the parasites instead of three, that’ll just get longer and longer. Then it takes five days, and then eventually it’s ineffective. There’s a hunt now for new types of treatments, which will probably come into play within four or five years’ time. The constant research and innovation around developing new drugs is critical. Same with the vaccines. It has to be constant until elimination is achieved.

Do we have an idea if climate change will affect outcomes? We don’t really know. There’s been some modeling, but the assumption is if it gets warmer, some places that have seen fewer mosquitoes—Greece, for example, which was one of the last places in Europe to eliminate malaria—might see it coming back. The average temperature rise or the ability of the mosquito to reproduce, for example, is changing with climate change. The modeling assumes that that will probably help in some parts of the world, but hinder in others and create greater problems.

On the positive side, as people tend to cluster more in towns and cities, the potential for keeping those areas malaria-free gets higher. First through spraying, because it can be done with a particular frequency in all neighborhoods. Second, as people accumulate wealth, they will find ways of elevating their houses, having better air flows, or bringing in air conditioning. That is what has reduced malaria in the United States—the screening of houses and air conditioning—along with fogging with insecticide. As that happens elsewhere in the world, we will see towns and cities improve, and then the focus will be more on the rural areas, where there will still be spread.

What about genetically modifying mosquitoes—do you think that has potential? It’s controversial. It has to be done species by species. If you eliminate enough of the mosquitoes that can transmit malaria—it’s something like 2% of the entire world mosquito population—you can actually eliminate malaria. Basically you tamper with the genes of the mosquito, grow them artificially, and release them in the wild to mate. If you do it with the males that mate with the females, they’ll have an inhibited reproductive capacity, because they’re playing with the chromosomes. And then naturally they will die down, and potentially die out.

They’ve now adapted that. So if you want to reintroduce the mosquitoes after malaria has been eliminated, you can. You don’t have to kill off the mosquitoes definitively, but you can eliminate the parasite for a few generations. Some of these mosquitoes can reproduce ten times in a year, so all of this can be done pretty quickly. There are large-scale trials in controlled conditions in Italy going on right now, and they’re hoping to experiment with some in the wild as well.

There’s one company that has developed an effective approach to dealing with dengue fever in Brazil and in the Cayman Islands. Looking at the horn of Africa now, there’s a new variety of mosquito, more common in Asia, particularly in India, that has made its new home there. The same company that did the dengue work is looking at developing something for that new variety in Africa. That would be great, because you would be preventing an invasive species from coming in.

All of these strategies—nets, treatments and spraying, drug therapies—play together very nicely. It’s not one or the other, until such time that you can really focus in and eliminate in one geography after another.

Given that all of these strategies are working in concert, I know it’s hard to forecast the future, but how far away are we from a malaria-free world? Who knows when it will finally be eliminated. There’s some who believe it will never be eliminated. Certainly reducing malaria fast enough around the world has had a setback even before the pandemic. The idea was 75% reduction by 2025, 90% reduction by 2030, but we didn’t even get a 40% reduction by 2020 from the baseline of 2015. We haven’t yet seen the total impact of Covid on malaria. Over 90% of the nets that were sent out to be distributed were distributed. So something went right. But Covid is not over, and the health measures prevent easy circulation of health workers, amongst other things. We just don’t know the numbers here.

Another aspect is how to get more real-time figures. WHO publishes a report annually, which gives what the situation was like a year previously, more or less. That’s too long, because malaria can surge and drop very quickly. There is work being done on dashboards for managers and so on, so that they can see much more clearly and bring in information from different sources much sooner, and that at least in-country, they can have that information. And maybe we can accumulate some of it.

In 2007, Bill and Melinda Gates said they wanted to see an end to malaria in their lifetimes. That was figured to be sometime by 2040. Hopefully they live longer, because 2040 is a bit of a stretch this point. We don’t really know. What we do know is that with any let-up of the effort, we’ll see resurgence; any with increase in the effort, we’ll see drastic reduction. The issue is, in a time when there’s been this deficit financing of Covid mitigation or relief, how are we going to see any appetite for further public health measures? Maybe there is a way of dealing with both together. Like Covid, malaria is very much a community-based thing. You need community action and community activity. If you double down on both Covid and malaria, you will get the double dividend for both.

When is difficult to predict. Back in 2015, we said 2040. The Lancet commission that came out two years ago suggested 2050. WHO’s own estimates don’t predict, because they don’t like to predict. But it’s a question of setting a target and aiming for it.

Are there certain countries you have your eye on that are on the cusp of being malaria-free? I think we can look to other Central American countries very quickly: Guatemala, Honduras, Costa Rica, and Panama. Nicaragua is a bit trickier. With particular effort, Hispaniola Island, Dominican Republic, and even Haiti could do it. The are central Asian countries that are very close. In India, you can look at a state like Odisha in eastern India, where state government has been very effective at rapid reduction of malaria, and particularly focused on the tribal areas and communities in remote areas. They have managed to focus there, and they have done extremely well.

The more tricky ones are probably where the highest burden is. That belt goes from the coastal areas of west Africa across Cote de Ivoire, Ghana, Togo, Nigeria, Cameroon, Gabon, and then into Democratic Republic of Congo, Uganda, and South Sudan. All these countries that have high burdens need to drastically reduce that burden. Whether they have the right tools, the right financing, and the right passion to do that is a different question at the moment, but that’s where a huge difference can be made.