Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

What Could Go Right? The end of AIDS

Dramatic progress in sub-Saharan Africa means it could be possible, soon.

This is our weekly newsletter, What Could Go Right? Sign up here to receive it in your inbox every Thursday at 6am ET. You can read past issues here.

The end of AIDS

Just four decades ago, a mysterious disease began receiving widespread attention in the United States when gay men started to die in New York and California. Scientists had not yet determined the underlying cause or realized that what was in fact a virus was quietly spreading among many subgroups. A stigma developed that persists even now.

By 1983, HIV—the virus that causes AIDS—was discovered and named by scientists at the Pasteur Institute in Paris. That same year, The World Health Organization (WHO) held its first meeting to surveil the global crisis, now understanding the multiple ways HIV could be transmitted, including sexual contact, needle sharing, pregnancy and childbirth, and breastfeeding.

Just two decades ago, more than 2.5 million people were contracting HIV, and 2 million dying of AIDS, every year. In parts of sub-Saharan Africa, spread was so bad that AIDS was reversing decades of gains in life expectancy. In Zimbabwe, for instance, 55 percent of all deaths were from AIDS in 2005.

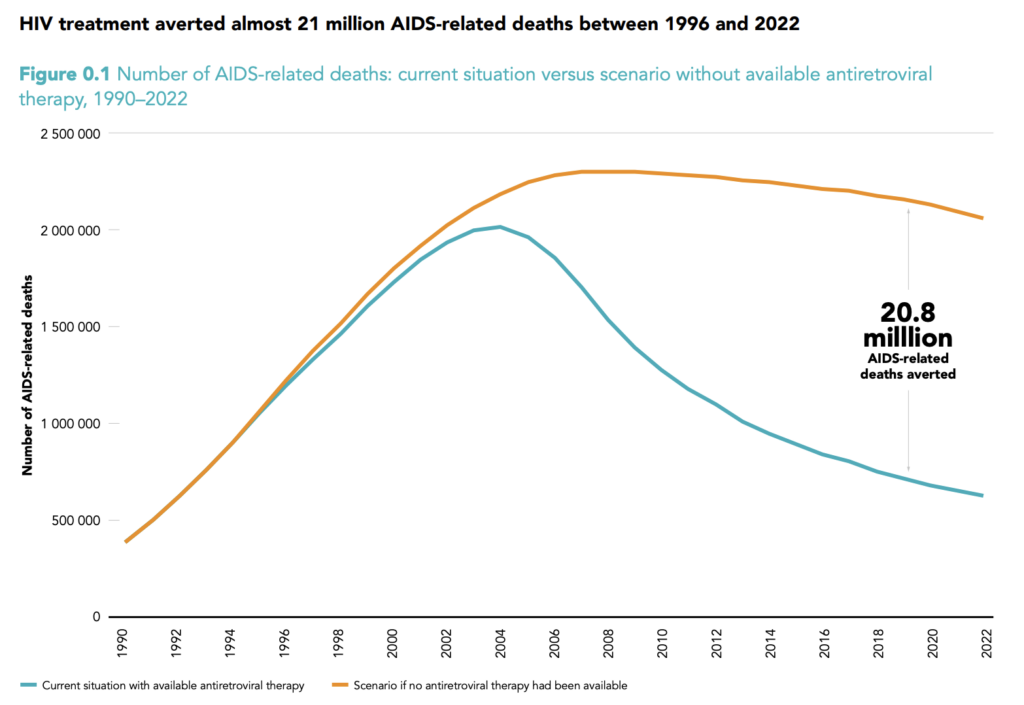

Fast forward to today. In 2022, according to a new UNAIDS report, global AIDS-related deaths have been cut by more than half, to around 630,000. Fewer people acquired HIV than at any point since the late 1980s, with the steepest drops in new infections among children and young people under the age of 24.

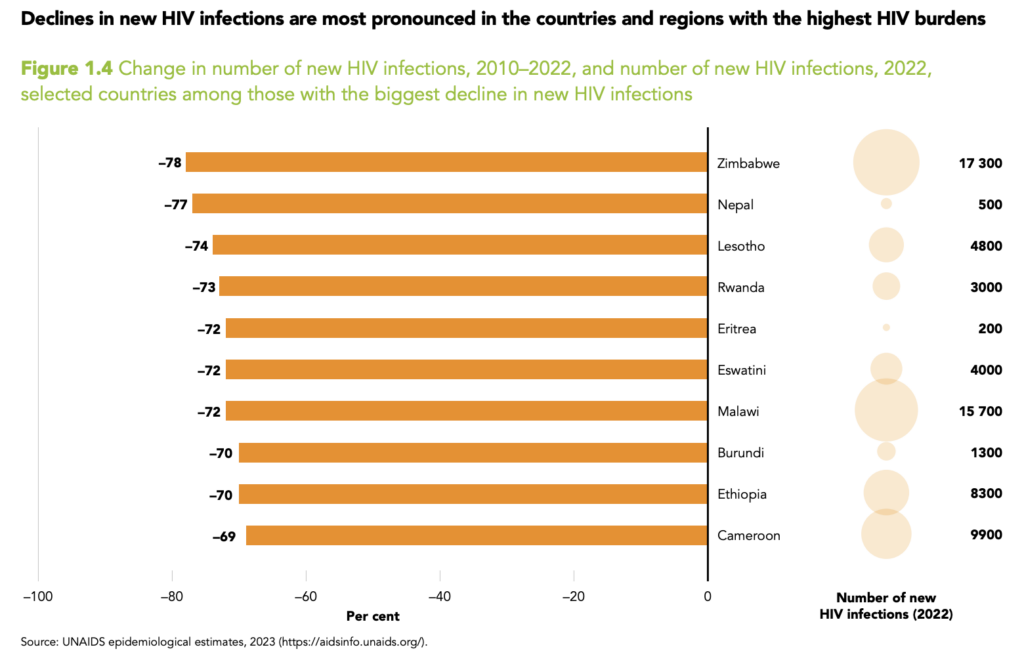

Countries with the highest burden are seeing the most improvement, like Zimbabwe, which has dropped new infections between 2010 and 2022 by a whopping 78 percent.

This situation probably seemed unimaginable in the 80s, and even in the early 2000s. How did we get here?

1. Antiretroviral therapy (ART): The first medication for HIV became available in 1987. (Younger readers may recognize the first name of the antiretroviral drug from Rent: “AZT break!”) As the years went on and ART was improved upon, it transformed HIV/AIDS from a terminal condition to a chronic, manageable illness. HIV-positive used to mean that the chances of survival beyond 10 years were slim. Now, people on ART live a normal lifespan.

As the decades passed, ART also became less expensive and more obtainable, particularly in low- and middle-income countries after 2000. There has been tremendous progress in expanding access to it, with 29.8 million of the 39 million people currently living with HIV receiving ART. That number has increased by 1.6 million people every year since 2020.

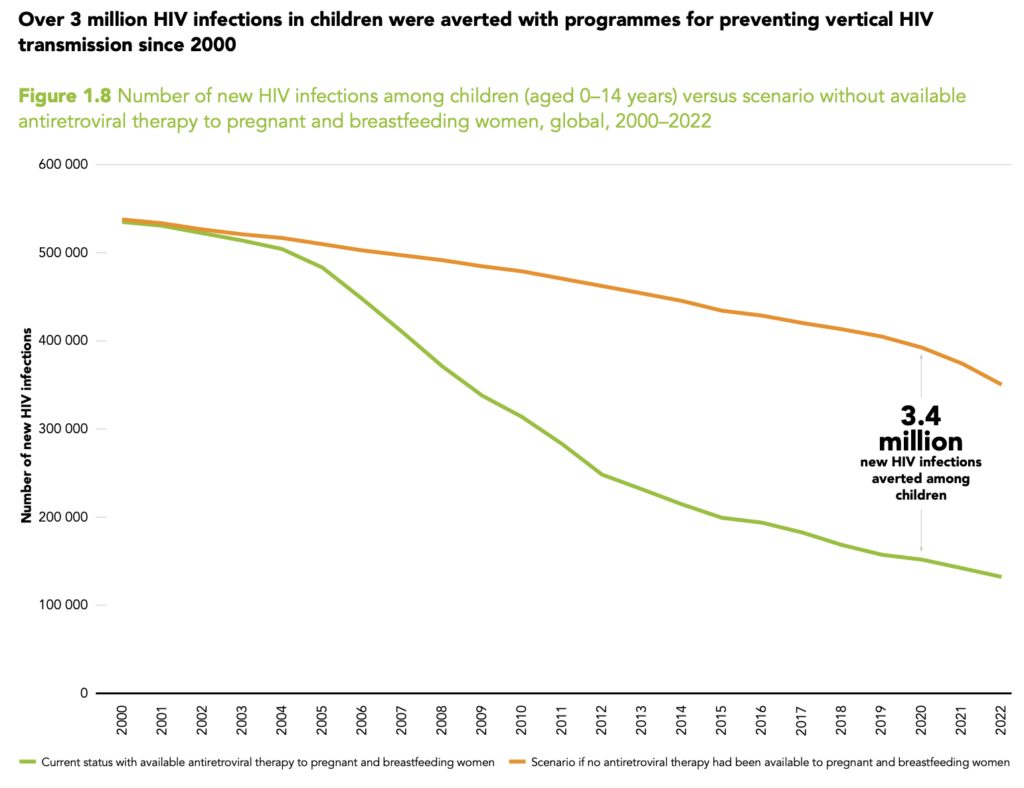

ART has saved many lives. Of the various strategies for mitigating the AIDS crisis, ART has been the main driver of cutting deaths in half. UNAIDS estimates that 21 million deaths were averted due to ART between 1996 and 2022.

And ART has cut down on transmission between partners as well as between mother and child. Doctors now administer antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy, delivery, and breastfeeding—HIV-positive mothers these days can safely breastfeed their children. This has limited new infections of infants.

2. Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP): In the last decade, two options for HIV-negative individuals at high risk of contracting the virus emerged: oral PrEP and the vaginal ring dapivirine. PrEP protects individuals almost 100 percent from contracting HIV. Women in Kenya, South Africa, Uganda, Zambia, and Zimbabwe can also use dapivirine, an insertable vaginal ring that is also highly effective (although not as effective as PrEP) at preventing contraction of the virus.

PrEP in tablet form is not as common in Africa, but a new injectable version, which lasts up to two months, is about to be rolled out across the continent. Experts have high hopes for it.

3. Education+: Aside from these drug-based developments, destigmatizing and increasing HIV testing, condom use, voluntary medical male circumcision, and non-punitive laws around homosexuality and sex work have all played a role in mitigating the AIDS crisis. Not to mention funding—lots of it—for NGO- and government-led programs.

Of course, there’s still plenty of bad. Even given the progress, one person every minute died of AIDS in 2022. Many people die needlessly, because they can’t access or stop taking antiretrovirals, likely due to affordability issues, surrounding stigma, or the medication’s side effects. While women and girls in sub-Saharan Africa account for 63 percent of all new HIV infections, adult men are significantly less likely than women to be on treatment in many parts of the world.

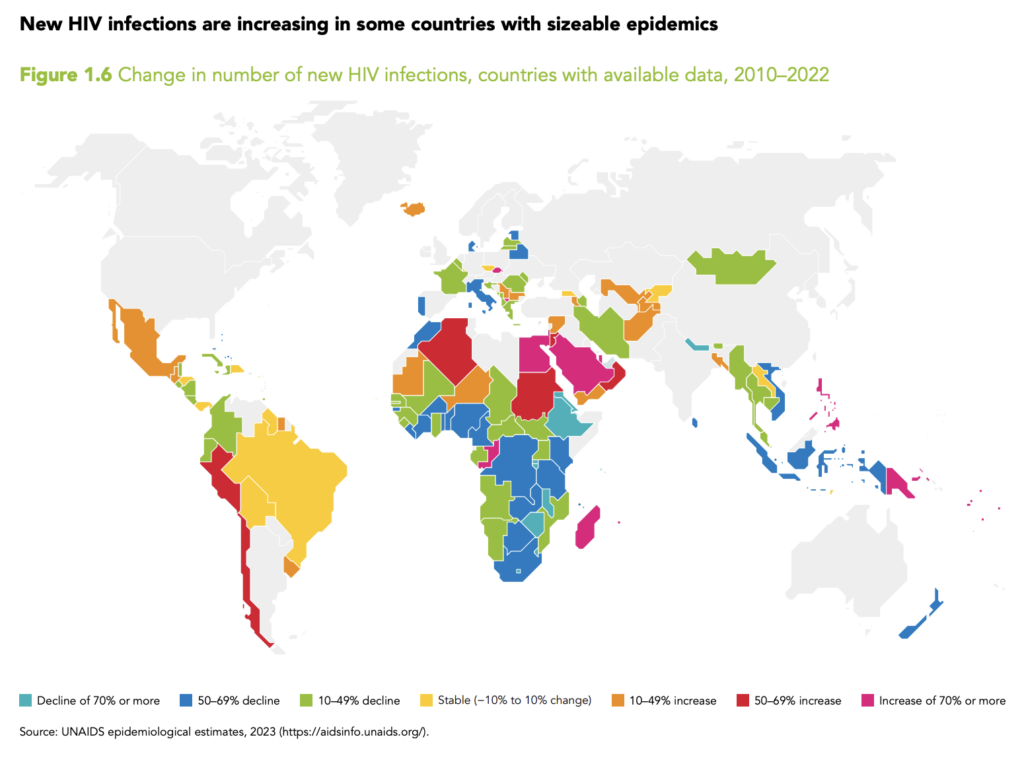

Big declines in sub-Saharan Africa have driven overall numbers of new infections down, but there have been increases in eastern Europe, Central Asia, the Middle East, and North Africa, which, according to UNAIDS, is due to a lack of services and “the barriers posed by punitive laws, violence, and social stigma and discrimination.”

Still, the UNAIDS report’s press summary emphasizes that there is a clear path to ending AIDS by 2030. Botswana, Eswatini, Rwanda, the United Republic of Tanzania and Zimbabwe, it says, have already achieved 95–95–95 targets, which means that 95 percent of people with HIV know that they have it, 95 percent of those people take antiretrovirals, and 95 percent of people taking antiretrovirals are virally suppressed—in other words, their immune systems will continue to function and they won’t become sick. And at least 16 other countries are close to the 95–95–95 targets, with Cambodia, Denmark, and Togo in particular within striking distance.

Some may be surprised to see Denmark listed. In a world where inequality in public health outcomes is routine, I was stunned by this from the UNAIDS report: “The proportions of people living with HIV who know their HIV status, who are on antiretroviral therapy and who are virally suppressed in eastern and southern Africa are almost the same as in the mostly high-income countries of western and central Europe and North America.” Which is to say, when it comes to AIDS, the global playing field is unusually level-ish.

Further progress will come from more of the above, in addition to changes in social attitudes around the LGBTQ community and sex workers (another reason why this newsletter cheers those on!). Research around ART given to HIV-positive infants, to cut down on mortality rates, is ongoing. And while scientists have yet to create an effective HIV vaccine, encouraging results from the first human trials of a candidate were recently published. The team behind it is now collaborating with pharma company Moderna to create an mRNA version, which may speed up the process.

The end of AIDS by 2030? It will depend on many factors. At the very least, it seems more than reasonable to expect continued—and previously unimaginable—progress.

Quick hits

- Ghana abolished the death penalty, the 124th country to do so and the 29th in Africa.

Below in the links section, solar canals, no-fuss psychedelics, a robotic liver transplant, and more.

Progress, Please

(Found good news? Tweet at us @progressntwrk or email.)

Other good stuff in the news 👽

Energy & Environment:

- A vast untapped green energy source is hiding beneath your feet | Wired

- Solar panels on water canals seem like a no-brainer. So why aren’t they widespread? | AP

- Amazon appears to be cutting down on plastics | Grist

- First-ever cargo ship powered by green methanol begins its journey | Interesting Engineering

- Iceland’s quest to use 100% of its fish waste | Hakai Magazine

- First white-tailed eagle in 240 years born in south of England | BBC

- Moth on brink of extinction found flying at secret Scottish site | The Guardian

Public Health:

- Why mainstreaming psychedelics isn’t generating a fuss | Axios

- Pfizer’s RSV vaccine recommended for approval in Europe | Stat News

Science & Tech:

- First-ever robotic liver transplant performed in the US | Interesting Engineering

- Cell ‘atlases’ offer unprecedented view of placenta, intestines and kidneys | Nature

- SETI advance hopes to parse alien radio from Earthly static | Interesting Engineering

- Botox to treat depression and anxiety? Experts have found a link. | National Geographic

Politics & Policy:

- Biden’s enhanced background checks appear to be working | The Trace

- Court strikes down limits on filming of police in Arizona | AP

- Next round of Michigan gun safety legislation to focus on domestic violence, suicide prevention | Michigan Advance

- Amsterdam to ban cruise ships to control tourism, pollution | Bloomberg

- EU passes law to blanket highways with fast EV chargers by end of 2025 | The Verge

- Lights out for incandescent bulbs | E&E News

Society & Culture:

- Biden picks female admiral to lead Navy. She’d be first woman on Joint Chiefs of Staff | AP

- Wesleyan ends legacy admissions after Supreme Court affirmative action ruling | Axios

- One college finds a way to get students to degrees more quickly, simply and cheaply | The Hechinger Report

Economy:

- America’s gender pay gap has shrunk to an all-time low, data shows | CBS News

- Chart: The economy is officially doing better than we thought | Axios

- Global economy shows signs of resilience despite lingering threats | The New York Times

TPN Member originals 🧠

(Who are our Members? Get to know them.)

- Fear not the Anthropocene Epoch! | James Pethokoukis

- Our democracy is menaced by two dragons. Here’s how to slay them. | Danielle Allen

- Being anxious or sad does not make you mentally ill | Arthur C. Brooks

- How to actually win back trust in news | Isaac Saul

- Colin Woodard on America’s many nations | Yascha Mounk

- We will never run out of resources | David Deutsch

- Will translation apps make learning foreign languages obsolete? | John McWhorter

Department of Ideas 💡

(A staff recommendation guaranteed to give your brain some food for thought.)

It’s the best and worst of times for climate change | Heatmap

We’re worse off than ever—but on a better track.

Why we picked it: Even amidst wildfires and heatwaves, when it comes to US climate policy, we’re in a completely different place than we were only a year ago. —Emma Varvaloucas

Until Next Time

Remember: when it rains, make like a deer. 🦌