Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

What Could Go Right? Everybody is asking for their art back

And more often than in the past, actually getting it

This is our weekly newsletter, What Could Go Right? Sign up here to receive it in your inbox every Thursday at 5am ET. You can read past issues here.

Everybody is asking for their art back

On Monday, British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak canceled a planned meeting with Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis after Mitsotakis made the case for the return of the Elgin Marbles in a BBC interview. The Elgin Marbles are statues that were taken from the Parthenon and the Acropolis of Athens in the early 1800s, when Greece was under Ottoman rule, at the behest of the British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, the Earl of Elgin. (It’s debated whether or not the Earl had permission from the Ottoman sultan, and whether that should matter.) They’re now on display at the British Museum.

Mitsotakis’ argument was nothing new. The Greeks have been asking for the Marbles back since 1835, after they declared independence. The more modern discussion about art repatriation—the return of stolen or looted artifacts to their country of origin—is not new, either. African leaders have been banging that drum since the 60s, with Belgium returning artifacts for the first time in 1976 to former colony Zaire, now the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

But Belgium’s move was the beginning and end of actual repatriation for a long while. French art historian Bénédicte Savoy writes in Africa’s Struggle for Its Art that it was the Greeks’ renewed request for the Marbles’ return in the late 70s and early 80s that distracted the world away from Africa, unwittingly stopping the discussion in its tracks.

Recently, however, not only has the discussion been taken back up, but also acted upon. A 2022 review of Savoy’s book in The New Yorker credits France’s president, Emmanuel Macron, with starting the trend in 2017, when “during a state visit to Burkina Faso, he declared that ‘African heritage cannot solely exist in private collections and European museums.’ The next year, his government issued a report that shocked many in the museum world, calling for permanent returns of looted art. France has since repatriated dozens of major works to Senegal, Madagascar, and Benin.”

It’s not just France. This year, the Netherlands gave back what is known as the “Lombok treasure,” precious stones and jewelry looted from former colonies Indonesia and Sri Lanka. Several institutions across countries, from Germany to the United States to Scotland, have returned objects from Nigeria’s Benin bronzes, a collection of several thousand plaques and sculptures that were taken during the British raid of Benin City in 1897. In 2022, Belgium returned another 84,000 artifacts to the DRC.

It’s not just Europe and its former colonies, either. Town & Country has a comprehensive list of all the unethically acquired art that has been returned in 2023 alone. It includes smuggled art in New Yorkers’ private collections that has been sent back to Italy; many artworks stolen by the Nazis given back to private Jewish heirs; a piece looted by the US army handed back to Iraq; artifacts taken during the reign of the Khmer Rouge returned to Cambodia; the remains of Native people returned to their Nations; and even a dinosaur fossil returned to Brazil.

I’ve seen arguments against repatriation framed in three ways. First, that art belongs to all of humanity, not just to the individual cultures that produced it—particularly when those cultures do not fall neatly onto the lines of modern nation-states. We should all have access to humanity’s creativity.

This point seems inconsistent. The vast majority of repatriated art has either gone back to museums for display in their countries of origin, or to heirs who then donated or sold the art to a museum. I’m not sure why the argument to keep, say, an African piece of art in a German museum is “universalist” while the argument to keep an African piece of art in an African museum is “nationalist,” if both museums are open to the public and able to preserve the pieces. As Howard French writes in Foreign Policy, why “should Africans have to travel overseas to see their own cultural products?”

There is also the fact that seeing art in the place it was made “hits different,” as the kids say. If the Elgin Marbles were returned to Greece, they would be kept in the beautiful Acropolis Museum, which sits directly across from the Parthenon and, as a setting for an immersive experience of the art, really can’t be beat. I had a similar feeling seeing ancient Mexican art in Mexico City’s own Museo Nacional de Antropología. It was an impactful experience.

The view from inside the Acropolis Museum in Athens

The second is the “slippery slope” argument. Writing in The Atlantic about what will happen to the Benin bronzes once they go back to Nigeria, Canadian commentator David Frum—whose parents collected African art—says, “A standard that art should belong to the present-day government of the place where that art was created centuries ago is not, to me, sustainable.”

Except that that isn’t the standard being proposed. Generally speaking, countries, museums, and cultural institutions are repatriating objects only if it can be proved that they were acquired involuntarily. There are plenty of other objects, ethically or legally obtained, that museums, particularly large ones, will continue to hold. Repatriation isn’t a suggestion to empty international collections. This is one reason why the British Museum, although not the British public, has balked at Greece’s request to return the Marbles for years, as an 1816 parliamentary investigation found Elgin’s actions to be legal after public outcry.

The third argument against repatriation is that it is just the latest trend in moral fashions. This one I think is true, but I see it as a good thing. As I have written about before, we no longer live in a world where invasions and the conquest of other nations are considered de rigueur. While it does still happen, it certainly doesn’t happen with the regularity it used to, and when it does, it’s notable and condemnable.

The world worked to create international law under which war is illegal. That it is now considering who has a rightful claim over the spoils of such wars makes sense. The repatriation cases that concern thievery by individual art smugglers outside historical conditions are even more straightforward.

Though there is an urge to frame these debates as another part of the “woke” movement, they have gone on longer than I think many realize. The African conversation began in the 60s. The US has been having their own with indigenous communities since at least 1990, when the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act was passed and Native Nations began to receive back millions of ancestral remains and other cultural items.

There are cases that are less straightforward. While as a half Greek I’m partial to the Elgin Marbles being returned to Greece, there is a 1963 law British Prime Minister Sunak is abiding by that prohibits the repatriation of art. The government could choose to review the law, of course.

Due to the back-and-forth over whether the Marbles were taken legally, during the BBC interview, Prime Minister Mitsotakis deliberately chose not to frame their return as an argument of “ownership,” but of “reunification,” since the Marbles are part of a set. (Other pieces of that set, held by Austria and the Vatican, have recently been sent back to Greece, but many others are still held by European museums.)

The Marbles aside, I see an art world trying to evolve past older standards of state behavior and follow through on course-correcting personal theft, which we have always considered wrong. I would call that moral progress.

As always, I’m curious to hear readers’ thoughts on this. Do you agree? Disagree? Comment below or email hello@theprogressnetwork.org to reach me.

Correction: Last week’s newsletter incorrectly worded the news of South Africa’s new parental leave policy. It is the first African country with shared parental leave, not the first in which both mothers and fathers are entitled to parental leave.

Below in the links section, an energy revolution in China, an end to malaria in Rwanda, a sustainable smartphone in the works, and more.

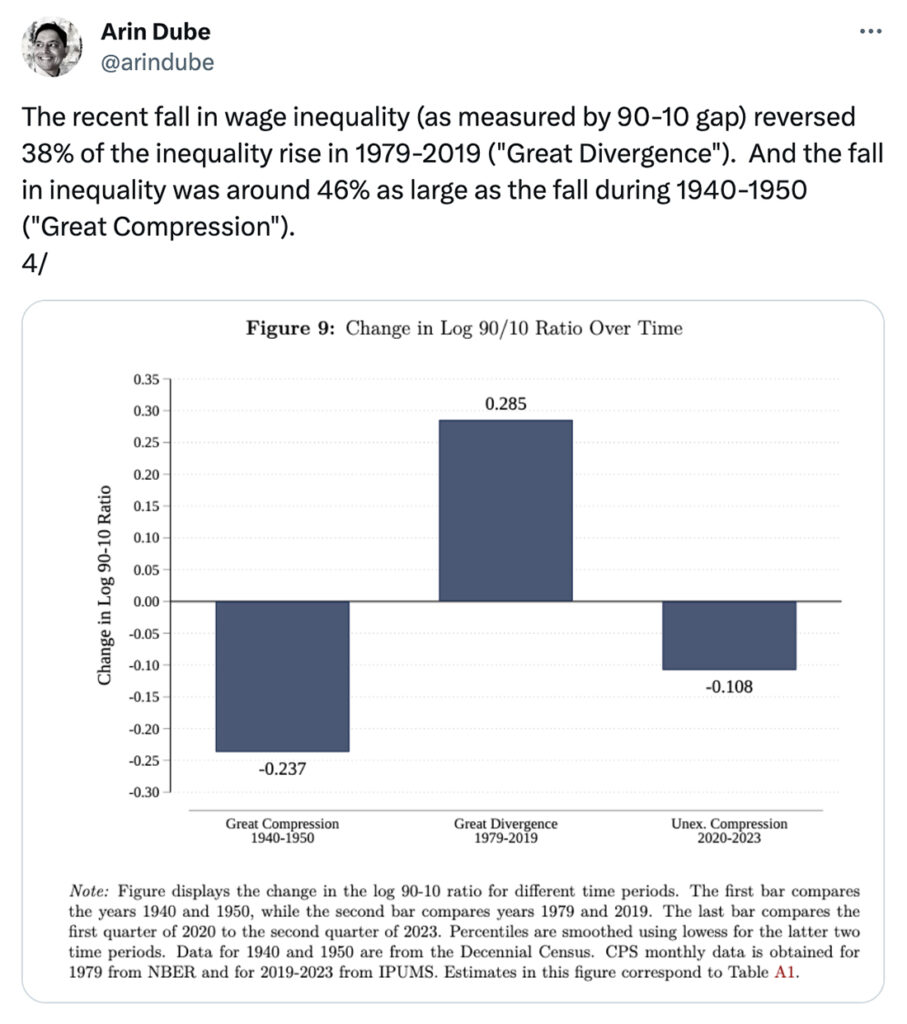

Wage inequality has fallen significantly over the past three years, according to the data in a new working paper.

Progress in 5 Minutes: Psychedelics to the Rescue

Long-overdue research about, legalization of, and enthusiasm for therapeutic psychedelics are spreading. | Read more

What Could Go Right? S5 E8

How much of a threat is AI to elections with new disclosure rules from big platforms in place? What’s going on with infant mortality trends? And why can’t we test for more illnesses at home? Zachary Karabell and Emma Varvaloucas are back to discuss the latest news stories we might have missed. | Listen to the episode

Progress, Please

(Found good news? Tweet at us @progressntwrk or email.)

Other good stuff in the news 🇫🇮

Energy & Environment:

- China’s remote deserts are hiding an energy revolution | Bloomberg

- Progress on climate change has been too slow. But it’s been real | The Economist

- Record 89% of Finland’s electricity from fossil-free sources last year | Yle

Public Health:

- Ditching fossil fuels improves health: Deaths from particulate pollution have dropped 16% since 2005 | El País

- Rwanda on track to achieve zero malaria in 2030 | AllAfrica

- Open defecation has fallen by 68% since 2000 | World Bank

- Egypt wiped out hepatitis C. Now it is trying to help the rest of Africa | The New York Times

Science & Tech:

- A new wave of startups is tackling a huge emissions source: wildfires | Canary Media

- What does a sustainable smartphone look like? | BBC

- Groundbreaking transatlantic flight using greener fuel lands in the US | BBC

Politics & Policy:

- Indonesia launches $20B renewable energy investment plan | Reuters

- New Jersey ended traffic deaths with a Vision Zero plan | Bloomberg

- The US doesn’t have universal health care—but these states (almost) do | Vox

Society & Culture:

- Gender equality gains momentum in sub-Saharan Africa | World Bank

TPN Member originals 🧠

(Who are our Members? Get to know them.)

- The Arab Israeli feels the pain twice | Thomas L. Friedman

- The Israel-Hamas hostage deal | Isaac Saul

- Four ways to be grateful—and happier | Arthur C. Brooks

- The Supreme Court needs term limits. Justices can do it themselves | Danielle Allen

- Staying humane in inhumane times | David Brooks

- Tim Urban on everything | Yascha Mounk

- Early college is the equalizer we need | John McWhorter

Department of Ideas 💡

(A staff recommendation guaranteed to give your brain some food for thought.)

Legacy media and political polarization | The Liberal Patriot

Why we picked it: I know you’re polarized, but what am I? John Halpin breaks down the data from a new survey that points to something surprising—legacy media consumers are more polarized than consumers of news from social media. —Emma Varvaloucas

Until Next Time

One more “make it more”: behold, the genesis of the silly geese god.

That is a good point, James! Intention matters, and we update as we go. Many fought for African art to be valued enough to be displayed in Western museums in the first place. Thanks for your comment.

I agree with your carefully considered arguments, but I think it’s the usual ‘retrospective impatience’ of some of the woke crowd that is so abrasive, ie in this case that this should never have happened, or that repatriation should have happened decades ago. I disagree with this, because museums were how we in the West learned about the world when there were real barriers to travel, and information. And we learned about them in good faith, out of genuine curiosity, not some strange sense of imperial superiority. It’s an arrogant kind of presentism to project onto the past the many advantages we now enjoy (to be able to see art/artefacts either in their original places, or virtually, via 3D scanning and the internet) which altogether make this less of an issue for us.