Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

17 fertility scenarios

A shrinking population seems likely to lead to a shrinking economy, where innovation grinds to a halt. Here are some other possibilities.

World population is widely projected to peak around 2050–90 at roughly 9–11 billion, with ~40 percent living in Africa. World population would then decline. But how long, and how far? The median respondent in my Twitter polls expects a population revival ~2150, and only 15 percent see population falling below 2 billion. So most expect this to be a mild and temporary problem. But I’m not so sure. In this post, I’ll review some possible scenarios.

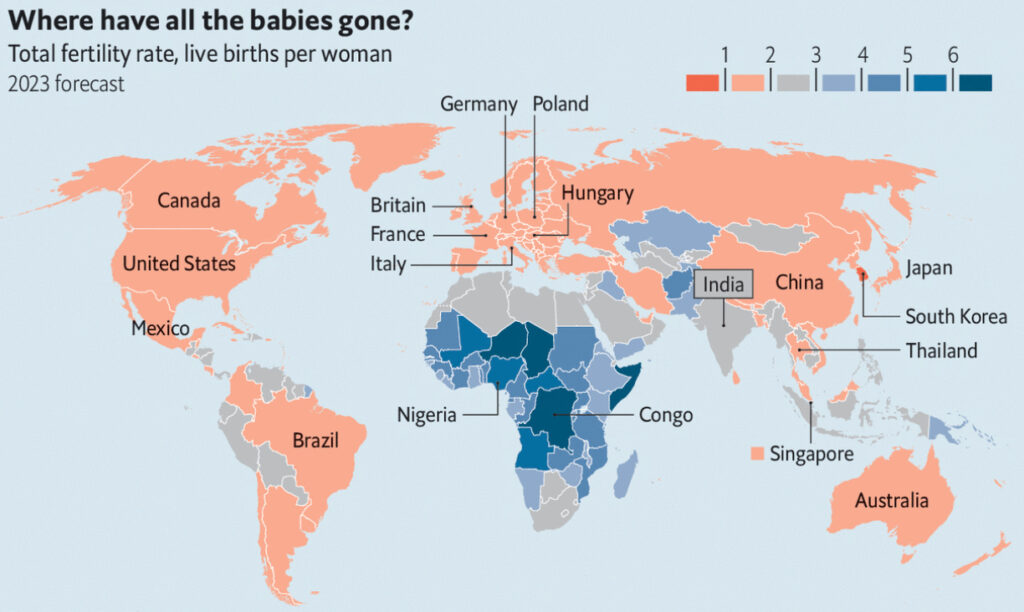

First, let’s set some context. Starting in France ~250 years ago, the number of children born to each woman in her lifetime, her “fertility,” consistently fell as incomes rose. Though some say this “demographic transition” is most closely connected to female education and access to contraception/abortion than to income. The most proximate causes I see are the high status of career success requiring high youthful efforts, a preference for fewer higher status kids, and an increasing taste for leisure.

Fertility usually falls more rapidly from 4–7 down to ~2, then falls more slowly below 2. Rich nations now average ~1.4, with some as low as 0.8. If world fertility averaged 1.4 for 25-year generations after a peak of 10 billion, humanity would go extinct in 1,660 years. If fertility instead averaged 1.0, that would take only 830 years. Most think extinction unlikely, and I agree with them, but such a risk shouldn’t be taken lightly.

As I discuss in my post “Shrinking economies don’t innovate,” it seems that a shrinking world population would robustly lead to a shrinking world economy, with innovation rapidly coming to a halt, which seems pretty scary. Given how naturally people resist change, it might be hard to restart a culture of innovation once it’s been long lost.

Okay, now we can list possible scenarios:

- Extinction: None of the other scenarios appear by a deadline, whose timing depends on just how low average world fertility rates fall.

- Poverty: When a shrinking economy gets poor enough, fertility might rise again, the reverse of how fertility fell as the world got rich.

- Big war: A big war might destroy much wealth suddenly, inducing poverty that increases fertility, and also maybe more directly increasing fertility.

- Wealth: Some say that even though, in the last few centuries, fertility has been falling with increasing wealth, that switches to fertility increasing with more wealth at a sufficiently high wealth level.

- Old moms: If tech allows longer lives, then female fertility might be greatly increased at older ages, with older parents retaining sufficient youthful energy to raise kids, and so kids after early career prep might become common. This tech must arise before the economy shrinks.

- Frozen eggs: Cheap, reliable egg-freezing (or egg-making) and IVF, together with older parents retaining sufficient youthful energy to raise kids, could also work. (Today 2 percent of US kids are via IVF.) This tech must arise before the economy shrinks.

- Robot nannies: Artificial wombs only ease a few months of parenthood. But robot nannies could help with all the rest. This must arise before the economy shrinks, and mainstream cultures would have to evolve to approve of their use.

- Last career: Artificial intelligence replaces humans on most all jobs, leaving parenting as one of the few meaningful activities that we are reluctant to give machines. Many then are willing and eager to be parents. This must arise before the economy shrinks.

- DNA selection: DNA that induces individuals to have more kids may get more common. This hasn’t happened so far in 250 years, but should eventually. This probably works mainly by making people care less about social status and conformity relative to having or raising kids. Such folks may be less cooperative, like dark triad types. They can’t be penalized for being anti-innovation until that restarts.

- Insular subculture: Initially small subculture(s) arise that highly value fertility, reliably keep members from leaving, and care little about what other cultures say of them. They probably achieve this by disrespecting outsiders, and defying many cherished outsider values. This tempts mainstream cultures to repress them, but such repression needs to mostly fail. As it wins, this subculture likely discards many elements of tech and culture that we now treasure; it can’t be penalized for being anti-innovation until that restarts. Maybe Africa creates insular culture to keep its fertility high.

- Parenting factories: Mainstream cultures change to allow or encourage raising kids in the equivalent of big boarding schools or orphanages. Via regimentation of kid lives, and low individual attention, these achieve strong scale economies, and thus greatly lower the cost of raising kids.

- Gap decade: Mainstream cultures change to taboo career training during, say, ages 16–26, pushing people to instead raise kids during this period. (Maybe induce triplets, to do all your kids at once.) Under this arrangement, mothers would no longer be at a career prep disadvantage. Financial assistance would be needed from families, nations, or investors.

- Gender roles: Mainstream cultures return to traditional gender roles, cutting the status of female career success, relative to parenthood. This discourages most women from early career prep. Contraception and abortion might also be discouraged or banned.

- Nation subsidy: Some nations subsidize raising kids at levels much higher than tried so far, paying for this with high taxes. To prevent nations with falling populations from grabbing this nation’s expensively made young adults, such emigration is either prevented by force or highly taxed. Emigration taxes might start when local fertility is high. World culture evolves to not see such policies as “coercing” women into motherhood.

- Kid debt/equity: Some nations let parents endow their kids with debt and equity obligations, selling such assets to investors to pay for their parenting expenses. Such nations use force to prevent such kids from emigrating to nations that would let them evade such obligations. World culture evolves to not see such debt, equity, and emigration blocks as “slavery.”

- Age of em: A world of brain emulations arises, and most humans convert to becoming ems, or emulated people, after which far fewer care whether the remaining humans eventually go extinct. This must arise before economy shrinks.

- Min parenting: The cultural trend of the last century toward more intense parenting reverses, so that parents become okay with paying much less attention to each kid. They are then willing to have more kids.

(See also: Noah Smith on fertility.)

Fitting 2,732 responses to 24 polls, here’s the relative likelihood, desirability, and story quality of these scenarios (excluding number 17, which was a late addition). The max for each is 100.

This article was republished with permission from Overcoming Bias. It has been edited from its original version.

Why worry about human extinction due to people wanting less children with climate crisis so obviously ramping up? Maybe that is one reason people are deciding to not have children. Also, if innovation is the concern look where unwise use of innovation has gotten us? Life is easier for a select few and it is even getting harder for the select few. I just don’t get the concern in this thinking.