Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

Now is the best time in history to love and be loved

The incredible social and human rights improvements over the last two centuries are powerful evidence that further progress remains possible.

You don’t have to travel too far back into the past to find evidence of widespread and systemic romantic misery. To visit England at the dawn of the Industrial Revolution would be to visit a world where women, and most especially poor women, were the unrestricted property of their fathers, and then once handed over—or sold—to a husband lost any vestige of control over their lives.

Throughout much of the 1800s, the average wife was prohibited from owning property, making a will, traveling freely, controlling her reproductive destiny, or leaving an unhappy or dangerous marriage. If she were married to a particularly brutal man, she had absolutely no legal protection from marital rape and could be forcefully dragged home and beaten half (but not completely) to death. Should the brute of a husband tire of a troublesome wife, he could sell her on the open market, presuming he first announced the proceeding sale through printed poster or public crier. To quote Ian Mortimer in The Time Traveller’s Guide to Regency Britain, “The wife must be sold openly—in a marketplace or public house—so that the public can witness the proceedings. She must be led to the place of sale with a rope halter around her neck or, in some places, around her waist. Sometimes the rope is tied up to some railings or a post. She must be sold to the highest bidder, and there can be no reserve.” Whether the husband threw the kids in with the closure of the transaction was entirely at his discretion.

While examples like these feel so culturally remote as to be totally unimaginable, they were the norm only 200 years ago. For nearly the entirety of the last 10,000 years of settled civilization, how we expressed our emotional and physical love, how we identified, how we partnered, unpartnered, did or didn’t have children, was strictly controlled.

It’s tempting but wrong to see the scale of these examples as relics of deep history, a primitive time long before anything we’d recognize as modern. In truth, we’ve only begun to claw back the humanity of love from the clutches of archaic culture. As recently as 1952, brilliant British mathematician Alan Turing was prosecuted for homosexual acts and elected to receive forced sterilization in place of a prison sentence as the lesser of two evils. That’s how the society of one of the most developed countries on earth treated one of its most brilliant minds—a mind that helped break German encryption and contributed to winning World War II—just 71 years ago.

When we look back 200 years, many of our current social victories in the progress of love feel unintuitive to comprehend as victories, largely because we see them, and rightfully so, as triumphs over unquestionably egregious conditions that should have never existed in the first place. However, the incredible social and human rights progress over the last two centuries is powerful evidence that further progress is possible, a mission to continue advancing.

The bad got less bad

Progress in nearly all aspects of love, although hard-won, has advanced dramatically over the last 200 years. Granted, the progress didn’t come fast enough, equitably enough, or ubiquitously enough, and there is still much progress to be made, but advancements have been made nonetheless, and they are continuing. In large swathes of the world, long gone are the days when you could sell your wife on the open market or even when physical violence against a partner, and particularly against women, was a tolerated part of everyday life. (Although rates of domestic violence remain high in certain countries.) With each passing year, the worst crimes against love, from bigotry to abuse and from class and racial stigma to rape and forced marriage, have become more culturally abhorrent and legally impermissible.

We are abandoning turning our noses up at the idea of interracial love. Between 1958 and 2021 in the United States, for instance, the percentage of people polled by Gallup who supported interracial marriage grew from 4 percent to 94 percent. Perhaps more astonishing, the approval rating grew by 1 percent annually from 2013 to 2021. Support for same-sex marriage has also improved dramatically in the US over the last decade, climbing from a low of just 27 percent in 1996 to 71 percent by 2021.

While acknowledging that serious challenges remain, the LGBTQ community has seen significant and sustained progress both in the US and globally. Today the vast majority of the world, excluding most of Africa and the Middle East, has decriminalized same-sex relations, a painfully low threshold for celebration but an indicator of hope that a better world for the LGBTQ community is possible, particularly in countries that have resisted progress on LGBTQ equality and legal protection most vehemently, and the longest. Whether you’re a woman, man, or identify otherwise when it comes to love, the grand narrative of the last century has been one of unfavorable laws and cultural conditions retreating and a more positive, supportive, legally protective, reverent, and equal world gaining ground.

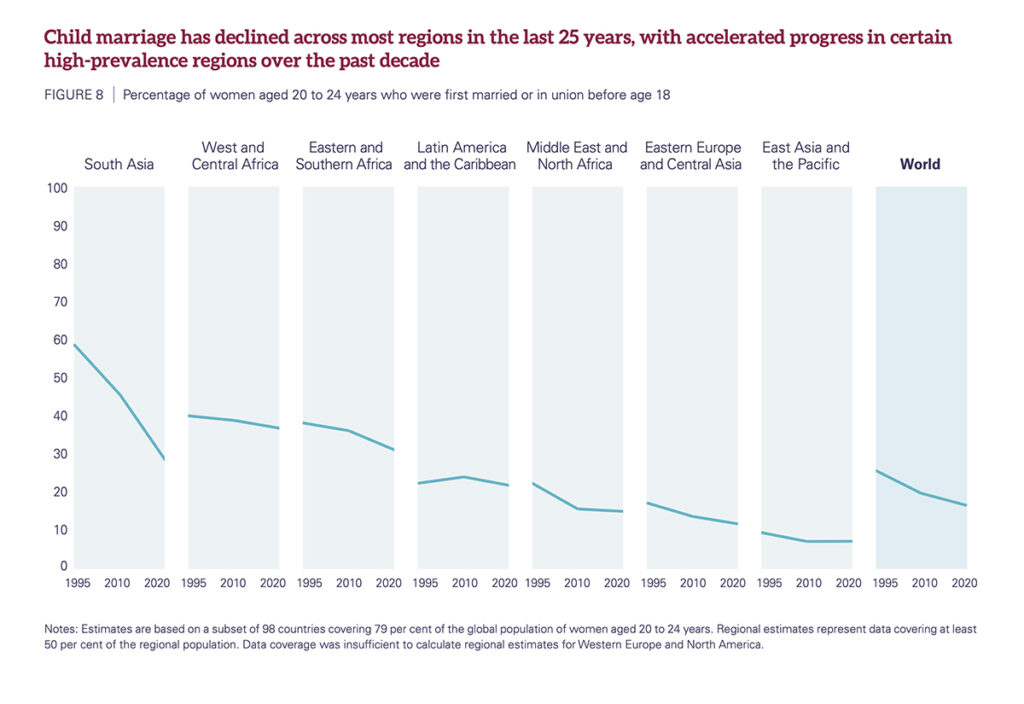

Another area of global progress in love is the reduction in marriages of girls under the age of 18. UNICEF estimated in a 2021 report that 650 million women alive today were married before their 18th birthday, with the vast majority of those marriages occurring in low- and middle-income countries, and with the largest global proportion, 47 percent, in South Asia. In Sub-Saharan Africa, some 34 percent of girls experienced child marriage, with the rate in Niger and the Central African Republic as high as 76 percent and 61 percent, respectively.

The good news is that globally, cultures are shifting away from an acceptance of child marriage in every region, with progress in South Asia being significantly pronounced. Across the greater South Asia region, child marriage has declined by more than a third, from nearly 50 percent a decade ago to 28 percent today. While many countries still have high rates of child marriage—one in three marriages of a girl under 18 years old occurs in India, for example—the global trend has been a sustained decline.

And the good got better

The progress of love isn’t just a story of bad things getting better but also one of people being able to connect digitally and in person, a story of shrinking barriers to love. Throughout the world, expensive long-distance phone calls have been replaced by extremely inexpensive audio and video calling, while airfare costs have been trending downwards for 100 years. There has never been a better or more accessible time to connect with the people you love.

Physical love and our ability to control our reproductive destiny have been transformed in less than a lifetime, with the number of women using modern contraceptive methods in the US climbing from 49 percent in 1965 to 66 percent in 2019. Even more remarkable has been the progress in contraceptive use in low- and middle-income countries over a similar period. In 1976, for instance, just 5 percent of Bangladeshi women were using modern contraceptive methods to plan their families; however, by 2019, the rate had climbed to 59 percent. For people across the world, but particularly in low- and middle-income countries, being able to share physical intimacy while planning their families has allowed for smaller, better-educated, and more economically productive families—powerful drivers in improved family living standards.

Progress forward isn’t progress completed

While humanity has made truly incredible progress toward building a more open, tolerant, safe, respectful, and equitable global culture, we’re still a long way from mission accomplished. Progress forward isn’t progress completed, and we shouldn’t mistake the ground gained as a guarantee that further progress will unfold without active effort. In many parts of the world, women and members of the LGBTQ community still experience cultural and institutional challenges and inequalities; still, conditions are improving. Regardless of your gender or sexual orientation, if you had to pick a year to be reborn into a random city in a random country, 2023 would be the year to pick. Today the average child is being born into the most inclusive and tolerant time in human history.

Little of this progress, however, was easily won, and we shouldn’t take for granted that the progress of love will march ahead without continued rejection of the arcane and barbaric social and cultural forces working against it, which have haunted humanity for millennia. If we do manage to continue to push forward many of these positive trends—and indicators are currently strong that we will—the next generation has the potential to be born into a much better world to love and be loved.