Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

Bridging Our Divides

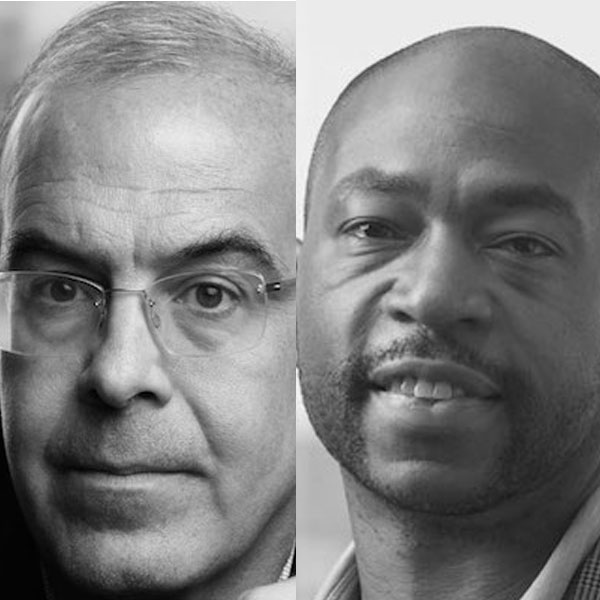

Featuring David Brooks and Theodore R. Johnson

The United States is a country divided, characterized by collapsing levels of trust in our institutions, in our politics, and in each other. How did we get into this mess, and how do we get out? Join The Progress Network for a conversation with TPN Members David Brooks and Theodore R. Johnson, hosted by our founder, Zachary Karabell, centered around this question. They examine ideas for how to bridge our divides at both an individual and collective level.

This conversation was recorded on December 21st, 2020.

Prefer to read? Check out the Audio Transcript

Emma Varvaloucas (EV): Hi, everyone. Welcome to The Progress Network’s second event, Bridging Our Divides, with David Brooks and Theodore R. Johnson, two of our wonderful members. There’s always a little bit of a lag between when we go live and when people are able to use their join link. So we’ll just give people a couple of seconds to start filling in the room here.

And as we do that, a couple of tech things. So, we’ll be talking for about 45 to 50 minutes. And after that, we’re going to be taking questions from the audience in the last 10 to 15 minutes. You can use the Q&A function. If you’re on a desktop, it’s on the bottom of your screen. If you’re on mobile, I believe it’s on the upper right-hand corner. You can use the chat function to chat with other attendees, or just share your thoughts generally about what’s being spoken about. But if you have a question you would like to be answered, please make sure to use the Q&A function. You can send those questions at any time and we’ll be taking them at the end.

And with that, Zachary is going to give us a little bit more of an intro of The Progress Network and what we’re about, but I’m going to introduce you to our panelists.

So first we have David Brooks. You likely have read his work in “The New York Times. He does twice weekly op-eds. And he’s been writing for them since, I believe, 2003. Is that right, David? Excellent. He has written a slew of books, most recently “The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life.” And very pertinent to this conversation, he’s also the executive director of Weave, the social fabric project at the Aspen Institutewhich is aiming to repair America’s social fabric.

And our second panelist is Theodore R. Johnson. I think we’re going to go by Ted. Is that all right with you, Ted? Excellent. So Ted is a senior fellow at the Brennan Center for Justice at New York University School of Law. His work explores how race plays a role in electoral politics including things like issue framing and disparities in policy outcomes. And Ted has a book coming out, I believe in June. It’s called “When the Stars Begin to Fall,” and that’s about building a truly inclusive national solidarity, which is definitely something that Ted’s going to be talking about tonight, and probably other themes from the book as well. And he has also written extensively for publications. So you can check out his work online.

And with that, I’m going to turn it over to Zachary, the founder of The Progress Network.

Zachary Karabell (ZK): Thank you, Emma. And thanks David and Ted for joining tonight. Probably one of the last events any of us will do for the year. So hopefully we can usher in the end of an annus horribilis with a certain amount of hope about the future. We clearly have enough despair, dystopian despair. And the whole point of The Progress Network, of which both of you are thankfully members, is that no matter how grim things are in either the way we tell it or the way it actually is, the future part of it’s unwritten. And it’s up to each of us to write that. So the future is not—unlike “Lawrence of Arabia”—the future is not written. It is up to each of us to determine it, and it can have a variety of outcomes, right? It could be as bad as we fear. It could be as open and embracing as we hope. And in moments where cultures—and I think right now, American culture, Western culture, maybe to some degree global culture—is admittedly in a dark place, pandemic-induced, partisan politics-induced you know, you name it, then the imperative for trying to see a pathway that is more constructive, I think, is vital.

I mean, my take has always been, if we’re all going to hell in a handbasket, it won’t be for lack of a lot of voices saying that we are. So it’s not going to take us by surprise. I personally, and the point of The Progress Network is I don’t really have anything to add to that narrative. If it’s right, it’s right. And again, it’s well covered. But if there’s another narrative, we should probably be thinking about that somewhat constructively.

So, you know, on that note, and on this day—we’re recording this, for those who are listening at another time on the eve of the winter solstice. Solstices are typically times when people think about change and inflection points. In the light of what I’ve just said, the winter solstice is the end of the darkest moment, literally, right? It is the end of the shortest and therefore darkest day of the year, at least in the Northern Hemisphere it is. And it is the beginning of a winter season, but it’s also the beginning of that beginning to change. So maybe there’s some poetic justice in doing it on this evening. It’s also, you know, at the heart of the late 1960s and early 70s, when American society, but also European, was roiling, right, in intense conflict with itself, and people with each other, to the point where people were really thinking whatever experiments—whether it was France, Mexico, the United States—that we were on the edge of an unraveling that was going to lead to revolution and change and more heartbreak. There was also, you know, the feeling that it was the dawning of the Age of Aquarius, right? That this was going to be a new period of hope and love and peace, and I’m not just talking about the silly musical, “Hair.” But we’re also on the night of a winter solstice when Jupiter and Saturn have come closest together as they will for 800 years. I don’t know what that means, by the way. I’m just throwing it out there as another kismet possibility for this conversation.

So with that, to go from the celestial to the terrestrial and earthbound, we’re going to structure this conversation as, like, a big picture, like, what’s going on politically and culturally right now. And then have it bear down a little more in terms of, there are things we might be able to do collectively, but also what might we be able to do individually to make sure that the sum of all our fears doesn’t come to pass? So on that, obviously a very divisive election. For some people it’s not quite over. Maybe you could both reflect for a moment, and I’m struck by this in looking at sort of message boards and discussion on both the left and the right, that each side, if there are two sides, but at least each major side has a perspective that the other in the United States is intensely anti-democratic, you know, that the Democrats essentially tried to steal the 2016 election away from Trump, or, you know, from the Democrat perspective, that Russia and Trump somehow colluded to steal the election away from Hillary. And then the replay of that in 2020 on the right, that the Democrats have now stolen the election away from Trump, and that both sides were interested in undermining the legitimate results of an election. How do you reconcile that mirror, right? Each of which is firmly convinced, in its own way, that those things are true. You want to start, Ted, and then David.

Theodore R. Johnson (TJ): Sure. So first, thanks for having me. David, it’s a pleasure to be with you. This is a moment of reflection and I think the solstice is perfect, that we’re here around this day to talk about this issue. So, a few things stand out to me. The first is that there is a paradox happening in the country right now that is marrying our best angels with our worst ones, our better angels with our darker ones. And this is happening at a time… You know, we opened the year with the president being impeached, with Ahmaud Arbery being gunned down in Georgia. On Memorial Day, George Floyd is killed. There’s a global health pandemic happening, and coronavirus is killing hundreds of thousands of Americans and hundreds of thousands more worldwide. We have two parties that are at each other’s throats, and that are willing to use the passions of the public and the instruments of government to have their way, in order to fashion our systems and our institutions in a way that gives them more power and influence and sway over the future of the country.

All of this is happening, and at the same time, in the midst of all this, we saw a summer of protest, where Americans across lines of race, class, religion, region, ethnicity, come together and essentially say to the state, the nation state, “you have exceeded your authority, and we are unhappy with how unresponsive you have been to us.” This is behind the veil of the Black Lives Matter movement, or racial justice movement, but I think at its core, it is a public expressing its dissatisfaction with the conduct of the state.

And so, while we have politicians playing out our worst impulses and using these things for partisan gain, we have a public that is both coming together in ways and dividing sort of following the cues of national and state leadership in other ways. And these two things are at odds with one another. They are in tension. And frankly, the two things cannot touch. This coming together, solidarity, multiracial, multi-ethnicity cannot come together at the same time as we see this division without one of the two things bruising, or both of them. And something’s going to have to give. In moments like this, usually transformative leaders are the ones that pull us from the moment and remind us of what our professed principles are as a nation. We are still waiting for that leadership, I think. And we’re certainly waiting for the public to sort of get on board with not viewing one another as enemies of the state and viewing each other as sort of citizens in solidarity with one another. Our politics are making it worse. I think we’re seeing the worst of it play out on social media and other places. But I don’t want to lose the optimistic things, the moments, the connections that have happened in the midst of all the divisiveness and the sort of enemy-making out of one another.

David Brooks (DB): Yeah, I guess for me, I’ve been helped this whole year by a book that Samuel Huntington, the late Harvard political scientist, wrote in 1981 called [“American Politics: The Promise of Disharmony”]. And he said that every 60 years or so America goes through what he called a moment of moral convulsion. And he said, it happened in the 1770s, It happened in the 1830s with Andrew Jackson, in the 1890s with The Progressive Era, the 1960s. And these are moments when people become indignant with power. They lose faith in society. An angry generation comes on the scene, intolerant to injustice. New communications technologies, come on the scene. Everybody’s angry, and they’re angry at a sense that the system just isn’t working anymore. And the good part about that… In 1981, he wrote, if the weird 60-year pattern continues, right around 2020 we’ll have another of these moments of moral convulsion.

And so, he was right. And to me, the moral convulsion didn’t start in 2020. It started around 2014. You had the rise of populist movements all around the world. The Indignados in Spain, saying to their leaders, “you do not represent us.” You had the killings of Eric Garner, and you began to have the real emergence of Black Lives Matter. You had the Trump movement beginning to get started. And so, what happened this year was, the earthquake was happening, and then we had a hurricane in the middle of the earthquake, which was COVID and the recession and Floyd, and that revealed all the fissures that were already exposed.

And so, the good news about that 60-year cycle, and I really do not believe cycles in general, but it’s that we’ve been here before. We’ve had a moment where everything seemed convulsant at those moments. When the old paradigms are breaking down, it seems ugly. In 1968, you could tell a much more dark story in 1968 than you could today, in my view. And yet, people figured this stuff out. And you have to have some faith in human ingenuity. The problem with our moment right now is the distrust in our systems is even higher than before. So you ask people, “do you trust government to do the right thing most of the time?” It’s like 19%. Distrust in each other is higher than before. If you ask people, “do you trust the people around you?” A generation ago, 60%. Now it’s about 33%. And the younger you go, the more distrust there is. And so one of the problems we face is that, you know, Ted talked about leadership, I’m waiting for leadership. And I happen to have a lot of faith in Joe Biden, but I don’t think people trust leadership anymore. I think they really only trust the people right around them. And so, that more than in other times when nations turn themselves around, it’s going to be more bottom up than top down.

ZK: I’m glad you mentioned Huntington. So, Sam Huntington was, as you said, a Harvard professor who wrote a lot about the clash of civilizations in the 90s after having written about these cycles before then. And I was a fellow at the Olin Institute, which is a national security Institute at Harvard, in the 1990s, while I was also writing for The Nation. I think I might have been the only person who was funded by the very conservative Olin Foundation and wrote for The Nation simultaneously. And Huntington knew this and thought I was just chronically wrong about everything. And I was, you know, much more in kind of my left, very self-righteous times phase, and you know, longer hair—I know that’s hard to believe, but it was a lot longer then. But with Huntington it always felt like, “I think you’re wrong and misguided and naive,” and all these things, “but I want the argument and the debate because I think there’s some value to be had by listening to these perspectives, even if I think they’re wrong.”

And it feels to me that in the 20 years, you know, since then—and there was low trust in government then, too, David. I mean, there was, you know, the Pew studies in the late 90s andyou know, big studies, “why don’t Americans trust government?” Military was the only thing people had faith in. But I feel like today there’s more of a tendency to dismiss as kind of liberal and bourgeoisie the very value system of, “I want to be juxtaposed and face-to-face with ideas that I find disagreeable, or I just think are wrong.” I mean, is thata quaint, elite, liberal mindset, Ted, that, you know, it was very nice when it was a bunch of white guys who essentially were in the same ecosystem? Because that is a way that a lot of that’s dismissed now. You know, the idea that I should be confronting, “I think you’re wrong, but I want to listen to you.”

TJ: Right. Yeah. So Huntingtonafter he had that seminal essay that led to the class of civilizations theory, or framework, he wrote a book, a longer treatise on that. And he titled the thing “Who Are We?” And I think this is the question that David talked about, that the nation begins to ask itself every 60, 70 years. And perhaps we’re in that cycle again. And it usually arises when the democracy expands, or the notion or the idea of who can be included as fully and truly American. When that expands a little bit, there are convulsions in the system. And so I do think when a bunch of, you know, elite white men are sitting around asking “who are we?” it is a different discussion than when you’ve got a black president, a Tea Party movementtwo parties that are further apart, polarized, and they are all holding the reins of power, asking each other, “who are we as Americans?”

They’re using the same words. They all say we believe in equality and liberty and freedom and prosperity, but the path to getting there is different. And who benefits from the large nests of the government also differs, and they’re different constructions. And so, we’re reduced back to this question of “who are we?” that Huntington posed a couple of decades ago.

So I do think that we are still wrestling with this question. I think the answer to that question, if we are successful, is what the American experiment is all about. If we can figure out how to create a truly liberal, egalitarian, multiracial, multiethnic democracy, in a nation of over 300 million people, we will have achieved something that no other nation can say it’s done. But if we fail, we will just be another story that nations tell one another and centuries ahead about failed experiments and theyou know, sort of the ego of people who thought they could do what human nature was never intended to. I buy the former argument, not the ladder, but it is a long, hard road to get there. But that question should be at the center of everything we do, politically and socially.

ZK: David, you spent years kind of arguing with Mark Shields, right? Like, that was a thing. Because there was this… I guess a sense that it wasn’t just good TV, but it was also, I guess, good for us, right? But is that a quaint notion?

DB: No, I think everybody I know likes to argue.It’s just that Jews and Catholics do it a lot more. No, I’m kidding. You know, that “Who Are We?” book that Huntington wrote later on was both extremely prescient and extremely wrong. It was prescient in helping us anticipate Trump because it was really not friendly to mass immigration, but it was extremely wrong in arguing that America is at its core, if I remember it correctly, an Anglo-Protestant nation, which is just not who we are anymore. And so, as Ted suggested, a friend of mine, Eric Lou says, we’re trying to do something really hard: create the first mass multicultural democracy with no majority group. Like, that’s just hard. We should cut ourselves some slack. And I do think… One of the things that I think we struggle with is finding a common narrative within which all voices can be heard.

And so, I was basically raised as an immigrant kid and I was told a narrative. And the narrative was that America is the Exodus story. We escaped oppression, crossed the wilderness, and came to The Promised Land. And the Puritans had a version of that narrative. A bunch of the founders had a version of that narrative. Benjamin Franklin wanted to put Moses on the Great Seal of the United States. Every immigrant group had a version. Martin Luther King talked more about The Old Testament than The New Testament. And it was Exodus all throughout the Civil Rights Movement.

I tell young people that narrative, and they look at me like I’m crazy. They say, “that’s the narrative powerful white men tell.” Like, “we’re The Promised Land? We’re not The Promised Land.” And so I tried to beat the Exodus narrative into them for a few years. And I finally got to respect them and say, “okay, we’re going to find a new narrative.” And I think we’re struggling to find that unifying narrative. I happen to think Lincoln’s second inaugural is a good narrative. It’s, “we had an experiment, a beautiful experiment. We’ve screwed it up in many, many ways. But there’s power in redemption.” But somehow we have not… If you don’t know what story you’re a part of, you don’t know what to do. And I think we’re struggling to find that thing that will unite across difference.

ZK: Anne-Marie Slaughter just pointed out in the chat what you just said, David, about Huntington. I mean, he did say, like, Latin Americans aren’t assimilable into the American experiment. So just just to echo that point…

TJ: Yeah, And so, this goes right to the point that David was making. I think the core American story is good and right. And I think, as David said, you can find that story in almost every group’s journey, to America, in America, and sort of being American. The problem is, the larger story that we tell ourselves is often too exclusive of the American story of other groups, groups that were late additions, or lately accepted, into the American story. So the core, I think, is good. The sort of fable of it is all good, the lessons to be learned. But the inclusion of it is the part that we’re still grappling with. And, that it is a story with a beginning, a middle, and an end, and not just a story that is complete, that we are the exceptional nation, and now let’s revel in our exceptionalism, but it is a story of error. It is a story of progress. It is a story of redemption, that is inclusive. And only when it has that richer context does the true core American story take on its fullest beauty.

ZK: You know, it’s funny, Ted—not funny-“ha ha,” funny-ironic—when Trump was elected and there was a degree on kind of liberal, coastal world that was shocked, right? Shocked at gambling at Casablanca. Shocked that that element of American culture—which has been nicely papered over in our story; it’s part of the story we don’t like to tell—was suddenly there. And a lot of African-Americans, a lot of racial minorities said, “look,” you know, “hello, like, this has been there all along. You guys have just been in denial about it.”

But then the flip side is, come the election of 2020, more African-Americans voted for Trump than voted for Hillary Clinton by 4 to 5%. You know, when you look at the national averages. More Hispanics, 4 to 5%. And even in those coastal cities like New York and Los Angeles, the percentage of people who voted for Trump was above 2016. In New York it was almost 6% more. In LA it was like one. In other cities, similar. So how do we account for that? You know, like on the one hand, there’s the, “Hey, wait a minute,” this kind of glaring example of the story we haven’t told on the part of a lot of people saying, “Hey, we’ve been saying this for years, you haven’t been listening.” But then come 2020, it’s not like that support went down amongst those very people. It went up.

TJ: Want me to jump in on this one?

ZK: Either.

TJ: So I will say, look, the anomaly isn’t, at least for black voters, isn’t Trump in 2020, or even Trump in 2016. The anomaly for black voters was really Obama in 2008 and probably 2012. If we go all the way back to ’64 and Goldwater vs Johnson in the presidential election, since then, from ’68 forward, about 11 or 12% African-Americans have voted for whoever the Republican candidate for president was. And only in 2008 and 2012 did that that number reduce because of Barack Obama’s candidacy. And so, all we’ve seen over the last two presidential elections in terms of African-American voters are black Republicans returning home after two presidential elections with a black president. So Trump’s ability to getyou know, 12, 13, 14%, depending on which exit polls you look at of African-Americans doesn’t suggest that there is a segment of black voters who have bought into the Trumpism, the Trump version of the Republican party, or the principles that he espouses, but rather that we are more partisan than we have been in some time.

And that partisanship cuts across racial lines, to some extent. Black voters are still the most monolithic block out there, but again, that one in seven, one in eight black folks voted for a Trump version of the Republican party is unremarkable in the sweep of history. And so, I don’t think we’re… The danger here isn’t that the Trump appeal is now spreading and we’ve got this to contend with. It is that partisanship and partisan polarization is now becoming a pandemic in and of itself in American culture, and attaching itself to our personal and social identities in a way that is really, really bad for liberal democracy.

DB: And I would say that I agree with Ted. It’s very easy to tell a story of incredible stability in the American political alignments, that all this stuff happens this year, and the Latino vote, black vote, gender gap—it’s like, whoa. It’s all kind of the same. The thing I do think is different is the class structure of our politics has changed. We have in our head from decades ago an idea that Republicans are the party of the rich, Democrats have some rich, educated folks. In Madison, Wisconsin, they have a lot of poor folks. Republicans have outer suburbs, and that’s still somewhat true but becoming less true. So I think four generations ago, Republicans won 87 of the richest counties in America. This time, Biden 87 of the richest counties in America.

Two things are happening. One, the what I call “bobos” or Richard Florida calls the creative class are just growing in wealth and power. And they’re concentrating in metro areas. And so you’re seeing this really powerful creative class elite. Then you have the Trumpian reaction against that elite, which pushes the corporate class blue, because they don’t want… Their basic CEO in Greenwich, Connecticut doesn’t want to be associated with Donald Trump. So Greenwich goes heavily democratic this year. And so, that shifts over, and as that happens, as the elite moves a little blue, economic elite, the working class moves a little red. And you get a cultural reaction, I think not so much in African-Americans, but I’m really struck by the Latino vote in the Rio Grande Valley. There seems to be real movement among working-class Latinos. And David Shore, a young but very intelligent progressive political analysts, said, “Democrats spent all this time dreaming of a multiracial working class coalition, and now it exists, and it looks like it’s on the Republican side. What happened?” And it didn’t end up looking like we thought it would look. And so I do think both those things are true.

ZK: I wonder, you know, you mentioned ’68 before, David, and there was an active debate over the summer: was the ’68 Redux, was it better, was it worse? And lots of people, including me, had their opinions about it. Clearly one huge distinguishing factors is we in 2020 know how 1968 turned out. So it’s easier to look back at that and go, “you know, it came out in the wash.” Whereas we have no idea how 2020 is going to turn out, in the future. And that’s the problem of, you know, we live in the present with no awareness of the future, but some awareness of the past.

But I do wonder whether, for both of you, and this is kind of the negative question, to Ted’s point of, you know, the better angels versus not, I mean, did we just get lucky in 1968, in 1861? Not that the Civil War was lucky, but you know, it ended with a certain amount of resolution. Although I guess today there’s some question of how resolved that actually was. Maybe, to Ted’s point, you know, nations have their seasons, right. And maybe this isn’t our season anymore.

DB: Yeah. Well, I certainly went through a period this year… Like, I’m not a declinist. I’ve argued against declinists my whole life. But when you look at trust, it’s very hard to build it back up. And I called all these social scientists: “How do you rebuild trust in a society that loses it?” And the social scientists were not really much help. Because they said, “well, we haven’t really seen it in our lifetimes.” Historians were a little better. Historians could point to England between about 1830 and 1848, when you had the sort of religious revival, Clapham Sect fighting for abolition. Then you had the charter, so The Union Movement, a working-class, bottom-up movement. You had the reform bills, a political reform movement from the top down. And that really did turn around that society. And similarly in 1890, and Robert Putnam has a book about this right now called “Upswing.” We had a cultural shift in the 1890s, the Social Gospel Movement, communitarian. We had a civic renaissance, boys clubs and girls clubs, Boy and Girl Scouts, the NAACP environmental movement, temperance movement, and then we had the progressive movement. And so you had culture, bottom-up civic, and then top-down political in that order.

And so, I do think it’s possible that people just figure it out. I have an innate faith in changing culture. A culture is a collective response to the problems of the moment. And while ’68 [inaudible], it really did produce amazing cultural shifts. I think of civil rights, I think of feminism, I think of all these things that came out at that time. And so I think we underestimate the extent to which culture is going to look very different in five years. Go to the Yale yearbook of 1968, and look at the photos of the men. Half of them have crew cuts. Half of them have long hair. By ’75 they all have long hair. You do have big cultural shifts when you live through these moments.

TJ: Yeah. And I think the important thing is that these big shifts don’t happen on their own. They’re kind of manufactured. And by this, I don’t mean that there’s sort of a puppet master making things happen and sort of changing society. But it seems like you have to have conditions, plus a national interest, plus a certain kind of leadership in order to transform a society over, say, in a relatively short period, like a decade. Usually, especially when you talk to political scientists, we tend to say, what the nation needs is a moment, a war, like, we need to find a common enemy in order to break down the barriers between us. And I don’t like that argument. Frankly, I think, you know, if COVID wasn’t enough to marshal the nation to sort of come togetherI don’t know that going to war with another nation is going to satisfy that. In fact, after 9/11, if you were a Sikh in America, you probably didn’t think that there was much national pride and unity in the days after.

But I do think that there are things happening in the ether, in our economy, in our social structures, around the worldcombined with the nation realizing that, if it wants to sustain itself, it needs to change. The Civil Rights Movement happened right alongside the Cold War. From ’48, when Truman desegregates the military and the federal workforce, all the way through to 1968, when the Fair Housing Act is signed. That 20-year sweep of strong civil rights statute, judicial holdings, and executive decisions didn’t happen because of epiphanies happening across white America. It happened because the nation realized that, as we told the world that democracy is the way of the future, that freedom and liberty is what people deserve, and a government that’s responsive to those folks.

And then the Russians or the Soviets could say, “and you lynched negroes that’s how much proof there is that your democracy is working so well. That narrative doesn’t work. And that presents a threat to the American identity and our national interests. And so, when you have those conditions plus the national interest, and then you’ve got strong leadership. Truman, Eisenhower, Lyndon Johnson—these were not men of leisure. These were men who made hard decisions, were not perfect by any means, but made hard decisions in favor of a more united country, or at least in favor of a country that took another step closer to its professed principles. Those three things are the things that, in my view, manufacture the change that makes us a more perfect union. And I think we are in such a moment now. The conditions are there, but we have to find the leader that will show the public, convince the public that it’s in our interest to behave in a way that’s more compatible with our principles.

ZK: You know, I wonder, for both of you, there is, like, two simultaneous arguments going on. One is, there’s a lot more that unites people in the United States than separates them, but that in sort of a media context, all that we pay attention are the things that separate. So that, you know, the othering is prevalent in our public discourse, whether it’s the othering of, you know, the blue states or people in my community where, you know, you talk about rednecks, or you talk about, you know, the South, you talk about the West, and guns, and it’s all with a kind of disdain that if it were racial would actually be… Would sound kind of racist, right? And if it’s in red country about the cities, you know, crime-ridden and socialists and anarchists and, you know, every time there’s a shot of the one square block of Seattle that was burning in the summer, it’s, you know, “Seattle is burning,” or “Portland is burning,” or whatever it is.

So there’s a lot of othering in our public. There’s not a lot of “us-ing.” But then it does leave you with a question of, is the notion that what unites us is greater than what divides us kind of a quaint pablum we tell ourselves? Whereas the othering that’s reflected in media land very prominently is more true? Which is it? I mean, David you’re, you know, you’re an increasingly unusual voice in media land in that you’re hard to put into a box, except on Zoom, where it’s very, very easy to put you into a box. Most people want boxes. The producers want boxes. Editors want boxes. They don’t want people who aren’t in boxes. And the whole point of The Progress Network is to talk about it. But I’m also pushing my own conceits here, right? Maybe what’s being reflected is in fact what’s real, that the othering is in fact more predominant than the us-ing.

DB: Yeah. I would say it depends on what system of reality. I mean, I can put myself in a box. I’m a Hamiltonian–Burkian. So I’m in a wig. My party died in like, [inaudible]. But I have a colleague who used to work at Weave and now works at Braver Angels named April Lawson. And she organizes groups of reds and blues. And what they do is they go into a town, and they go on social media, and they find the absolute craziest people they can find. Like 15 on each side. And then they spend a weekend together conversing. And then about middle of the day Sunday, they say, you know, “well, of course we get it together. But we’re the moderates. You should’ve picked the crazies.” No, you are the crazies. So, so much of what’s going on is performative.

You try and believe what the tribe wants you to believe. So much of it is dependent on distance. And so much is manufactured by people in my industry. But so that’s why I come back to local. And I think we’re going to have to start local because, you know, with Weave, before COVID, I would travel around the country through three states a week, and there was never a town I went to into that was as dysfunctional as Washington. Every town—and Jim and Deb Fallows, our friends, write about this as well—every town is working reasonably well because, you know, contact theory, the idea that when you actually talk to someone, you actually get to like them. It’s hard to hate at close range. That really is true. And so I do think, that’s why I continually go back to the hyper, hyperlocal. Because when you meet people, it’s really, they don’t fit your boxes.

Just to close, I was at a Trump rally, this was back in the beginning of Trumpism. I run into a lesbian biker who collected guns and converted to Sufi Islam after surviving a plane crash. Like, what box does she fit into? And she’s supporting Trump. And that’s every individual human being you meet doesn’t fit into a box when you actually get to know them.

TJ: Yeah, that’s absolutely right. I’ve got a friend I went to high school with a black woman raised evangelical Christian who converted to Islam in college, who is now an FBI special agent working on finding nuclear weapons, the trace of, like, the chemicals around nuclear and biological weapons, when they find sites around the world. So she is like both unbelievably un-American in her, sort of the idea of her. And there is no better perfect picture of what an American is and could be, and sort of all the identities wrapped up in who she is. And so this sort of gets to the question about the us-ing. The us-ing we’re trying to do in America is unnatural. Most nations bind over a religion or an ethnicity, they’re very homogenous. And all the social science suggests the more diverse a group of people are, in terms of a nation state or in a society, the more difficult it is to create effective bonds between those folks, because just the ontological marker of race, of gender even of religion, based on attire, et cetera, serves as dividing walls between folks.

And the only way you can break those down is through closer contact, and then through, again, strong leadership. And so the us-ing we’re trying to build an America is built on an idea. You know, if you subscribe to the things in our sacred texts, in the Declaration, the Constitution, the Bill of Rights, that’s supposed to be sufficient enough for you to be considered fully and truly American. And since the nation’s inception, and even in the decades beforehand, it’s never been sufficient to have the belief. And yet, we continue to say we are a nation founded on an idea. And we sort of guard who has access to the idea, who gets the benefit from, again, the largesse of the nation built on this idea. But if we cannot find a way to create the us out of an idea, which is, again, something that hasn’t happened before for a nation of our size and power then the American experiment is in danger. I believe that it’s possible, but it’s going to require a lot of sacrifice and forbearance to make it real.

ZK: I’m really glad you said that, and to kind of follow on that it struck me for years that part of that story, David, that we tell also glosses over a lot of how difficult it was to get to each successive, somewhat larger us. You know, that it wasn’t a kumbaya… It wasn’t like everybody read Burke and went, “oh, you know, we should all sit down and engage each other, even though we hate each other or have differences.” There was a lot of conflict to get to, if not concord, then kind of a live and let live. And I guess I wonder, you know, Ted, on this how do you talk to maximalists about minimal steps? You know, how do you convince people who have—and this is absolutely true for African-Americans demanding justice and demanding it now; it’s true for red America saying you know, the election was stolen; it’s true for blue America saying, you know, we need to have a progressive, you know, Green New Deal, even if part of the country doesn’t want it—how do we do that? Like, how do you do minimal steps in a maximalists culture?

TJ: Yeah. So I think the first thing is the minimalist and the maximalist, and all of the people around them, have to recognize that it isn’t necessary for them to agree, to sing “Kumbaya” in order for the nation to move forward. Like, they don’t have to get on the same page before we can move. So this is how I like to think of it: the maximalist, I call them truth-tellers, and the minimalists, I call them bridge-builders. And it’s not a one-to-one match, but the role they play in society, I think is about right. The truth-tellers, the maximalists are pointing in a direction for the nation based on a set of principles that they believe. And usually what we’re arguing aboutwhatever side of the vision you’re on, is usually about how to get to this more perfect union, and not that we want a more perfect union. We certainly have folks on the fringe who would rather kick all people of color out or re-install rigid patriarchy and keep women at hull. Those are the folks that are so few and far between, even if they have a big megaphone on social media, that they’re not the true maximalist. They’re actually detracting from the vision.

But those folks who may say Medicare for all, or those on the other side that say stronger second amendment protections, all of them are basically saying, we believe in a more perfect union, and these are the things we need to get there, in their construct. The bridge-builders are the folks who look at the sort of north star that these truth-tellers put in the sky and begin walking in that direction. And the tension, again, is about, “do we take a step southwest or northeast,” but moving in a direction to make the nation more perfect is I think, on the minds of both sides.

And so, to bring them together, I think the key is to recognize that we both want the same thing. We disagree on how to get there. But we both want the same thing. We are not there yet. What we actually believe—and by “we,” I mean the American public—believes that the other side is actively trying to destroy what we’re trying to build. And when we don’t have a common vision, when we can’t even see the better angels of the other side and recognize them as fellow citizens that want the same thing out of this nation, then it doesn’t matter about, you know, who the maximalists are, who the minimalists are, what direction they’re going, because no matter what step they take, even if it’s in the direction to our benefit, we will view that step as treasonous and as a threat to the nation. So we’ve got to reconcile that we all actually want the same thing out of this nation. And until we get to that very foundational consensus agreement, the other stuff is just fodder for battle.

DB: Let me spread a little optimism on you, Zachary. So, about two weeks ago, I called around to a bunch of senators, Republicans, and asked if they thought there was stuff they could get done with Joe Biden. And everybody I spoke to came up with the lists of things they want to do. Prescription drugs, immigration, at least DACA; obviously, infrastructure plans. And they came up with lists pretty easily of 16 bills that they thought at least, you know, eight, 10 Republicans could get on. And I think the Republican Party has become… The parties are further apart on culture than ever before, but not as far apart, I think, on economics as before. I think the Republican Party—I think I saw Avik Roy’s on this call; he would know better than I—but a lot of Republicans want to become that working-class party. And they’re quite willing to use government and even industrial policy to do it. And so, I think there are some options there.

And then I was on a call last week with the Problem Solvers Caucus. And that’s, I think… There’s several dozen house members, evenly Democrat and Republican, and eight to 10 senators, evenly Democrat and Republican. And the first thing I was struck by on the call was the intense bonds of camaraderie across party between these people. That they had really formed intense bonds and really a decision to get stuff done. And lo and behold, they are the ones who created this $900 billion compromise, or at least the framework for it. And you may not be happy with it. I’m not particularly happy with it, but at least it’s something that passed. And so, I do think there’s a group of people in the Congress who realize that leadership has just gotten too powerful. And Mitch McConnell has not allowed votes on bill after bill after bill, whether a Republican Senator or a Democratic Senator. And people came here to try to do stuff, most of them. And so I came away from these two interviews and sets of conversations a little more hopeful that it’ll be incremental, obviously, but it’ll be something. And I do think Biden is going to get some pieces of legislation passed in the new Congress.

ZK: Yeah, I wonder on that. Like, is there, and David, you’ve written a lot about this, about how to sort of from a moral framework, but also how to have conversations, right? How to listen, how to, how to speak. And I wonder if some of it is, you know, one, a watchword, which I find myself coming back to a lot these days, is a certain amount of humility and humbleness of, you know, none of us have the sole access to the truth, capital-T. That in order to work with others whose views you might find objectionable, it requires a degree—I suppose that’s in the trust category—of believing that they may indeed want the best for their country, the best for their family, the best for their community, and come up with radically different responses to that, but are not so othered as to be, you know, evil and dismissible. It would seem that having some of that is a necessary prerequisite, or at least trying to inculcate that individually. I don’t know whether that, you know… The question with the Problem Solvers Caucus is why are they not out—you know, I wondered about this with some of the moderates within the Democratic Party—why aren’t they pounding their own pavement? Are they pounding it, and the media is not listening? Are they not pounding it because they’re scared they’re not going to be heard?

DB: Well, I think it’s hard… A, they are trying, and it’s hard for them to get media attention. But it’s also true that it’s hard to go up against your own leadership. Your [inaudible] to lose committee assignment. It’s hard to go up against the people in the media who will pound you for being in the middle. I can tell you, because I’m this famous Burkian–Hamiltonian, I’m sort of in the middle now. And it was easier being on one side. I used to be on a team. It was easier. So for them, I don’t even have to get reelected. They have to get reelected. And they have to get reelected without being primaried. But Joe Biden is a problem solver. I mean, he grew up in an era when things were [inaudible], Ted mentioned all these things that passed in that 20 year window. The Fair Housing Act, the Voting Rights Act, the Civil Rights Act—that was Biden’s formative era.

And so he looks at this country, and that’s what he sees. An era where things worked and where there were actual [inaudible] in Congress. So in my view, and to go back to the maximalist–minimalist, I was coming into conversation during the middle of the real high points of the Floyd protests. And I remember a friend of mine said to me, “you know, people like us, we don’t really like a lot of the real anger that’s out there, but we would not all be talking about that without the maximalist.” But now it’s time for us to come in after with the inevitable, boring, incremental things. So I totally agree with Ted on the incremental rolls.

The one point… I would point people to a piece that was in the New Yorker at about that time by Hilton Als, A-L-S. And it was [“My Mother’s Dreams for Her Son, and All Black Children”] in America. And he writes about his past and his mother’s generation, which really was “just keep your head down and keep silent.” And Als’ point is that I would like to believe in that incremental faith, or even the Martin Luther King, but we have been made such refugees in this country, that doesn’t really work for us. And at some point, you have to say, not only “no” to the silence the system’s trying to impose, but the silence the older generation’s trying to impose. That was his point, and a very fine piece; I recommend it. And I think a lot of people, even in different races, have that same… A lot of young white people think “you guys are totally sold us out on climate change, XYZ. I’m not doing this silent, incremental thing for you, because I’ve never in my life seen that work.” And from their lived experience, that’s probably true.

TJ: Yeah. I think the… So, one, pragmatism just isn’t sexy. And people don’t get excited about small agreements. They get excited about sort of these sweeping packages or the fighting that prevents anything from happening. But the other part isthe politics of patience, that works unless you are the person with a police officer’s knee on the back of your neck. There’s no time for patience there. And, you know, in ’68, what sort of kicked off this, you know, some transformation that happens in the country, there is a summer of rioting, and ’67. And then again in April of ’68, following Martin Luther King’s assassination, that proceeds that transformation. And so, at some point, incrementalism, when it doesn’t serve particular groups, that group is going to let the nation know that what is happening is no longer acceptable. Prior to Truman’s desegregation orders in ’48 even before FDR, you had the Red Summer of 1919, racial riots across the country, police brutalityjobs washing off, fair wages weren’t being paid.

And so you have large amounts of protest and unrest. You have large amounts of organizing mostly happening, not by the men at the front of the movements, but by women doing grassroots mobilization in churches and communities through those institutions that bonded communities together, that led to these sweeps of transformation and societal change that the history books remember most. So, I think it’s in the eras of incrementalism where the nation becomes a little bit better, a little bit more perfect. But in the periods between those incremental steps, it’s usually very painful, especially for those excluded groups, those marginalized groups. And those groups do not sit quiet and wait their turn. They’re not opportunistic waiting for their their window. They are forcing the nation to move. They’re compelling the policy window to open. And so the incrementalism and the maximalism play off of one another and that allows the nation to move forward in a system designed to be very resilient and resistant to change.

ZK: Yeah, I mean, it could be of course, 20, 30 years from now, we will look back at these moments and see, you know, not the breakdown of a system, but the efflorescence of actual on-the-ground democracy, right? Where everybody believes as a birthright that their voice and their needs should be heard, deserve to be heard, will be heard. And in the moment, that can just seem like a cacophony of competing demands cascading against each other in a really violent way. Violent, emotionally. Violent, literally. But you know, there is a possibility that we’re so immersed in this literal explosion of conflict, or of “my voice, my needs, my demands, now. We have to fix climate change. We have to fix racial injustice. We have to solve the issues of the past. We have to be, you know, all of the ideals that we have thought we should be, and variants of that around the world,” right? You know, “I’m not going to be poor and bound by a caste system in India, or bound by a caste system in America, or bound by anything other than whatever it is that I can unleash of my own individualism,” which is so contrary to how most societies have ever lived.

You know, we have some more time for Q&A. There’s been a lot of stuff in the chat, which I think a lot of, you know, we have been looking at. David’s referenced some, Ted’s picked up on some of it, I have. So we’ve tried to kind of integrate subtly, multitasking as we go along, some of the stuff in the chat. There’s one question that in the Q&A about what might unite, you know, what might strengthen the “us” part, and someone suggested that poverty is something that cuts across region. It’s rural and white. It’s urban and African-American. It’s South Texas and Hispanic, and California and Latinx. It’s, you know, Asian and Chinatowns, meaning that there could be a degree to which poverty becomes kind of a unifying theme. It clearly was, I guess, briefly in 1965, the rationale for a whole series of expensive social programs. What do you think? I mean, is that feasible?

DB: Yeah, I would say people are united by common loves. And in most communities, they love their kids. So working on education and the status of children is something that tends to unite. They love their place just making a beautiful town, or a beautiful village. They love their work. And it would be very helpful if we did have economic security for people. And that’s something that has to come mostly from Washington, I suppose. Whether it’s through infrastructure or wage supports or [inaudible] credit or whatever you want to do. But I do think, you know, my Weavers, the people I go around and visit and try to celebrate around the country, they’re main focus is the marginalized. They work on the edges of society for those most left out. And if you had spent the last three years pre-COVID like me traveling around and talking to these people, writing stories, making movies about them, bringing them to audiences, you would be an extremely hopeful person. Because, a, they’re incredibly dynamic people. They really are people for other people. They live lives for others. They have this moral charisma. They have an extensive vocational certitude. I know why I’m here. I know who I’m serving. And they have a sense of joyfulness. And so it could be that the revival is happening. It’s just, it’s in Watts. It’s in McCook, Nebraska, it’s in Wilkes, North Carolina. And we’re sort of ruining that.

TJ: Yeah. The future blossoming of the United States is going to result from seeds planted locally, as David said. I think there’s absolutely a bottom up… It will need to be a bottom-up epiphany for the nation. I don’t think an issue’s going to do it. I don’t think it’s going to be poverty. I don’t think it’s going to be economic inequality. I think those things may cause people to sort of retreat to their community and look for purpose therebecause of all of the pessimism and, and bad news that they hear nationally. But I do think that some things, structural racism I think… There are issues that filter to the local in a way that prevents local community from forming because they’re exclusive or they continue to exacerbate the marginalization that David was talking about.

But when you are in these communities, you don’t see the division that you would expect to see if you live on social media or on cable news. So family, as David said, family is important. But the other thing is finding the new set of institutions. Church attendance is down. Boy Scout membershipsyou know, Shriners Club, bowling clubs, all these institutions that used to be places where the community would gather and build together are not there anymore. Those institutions from 80 years ago are gone, but what are the new ones? Is it Orangetheory? Is it yoga? Is it a book club, running clubs? What do the new types of social institutions that are smaller, more transitory, more malleable, flexible, and maybe even ephemeral, but the existence of these institutions is, I think, a fact of local communities. And so we’ve just got to find what they are and then leverage their existence in order to build out from them and restore the potential that is in our communities and in the country writ large.

ZK: And on that, there was a question in the chat about, particularly for rural America. And David, you know, you did a lot of traveling around. A lot of these narratives are perforce written by people in cities, you know, both out of intense social justice or privileged elites, but they do tend to come out of urban areas, a lot of these stories, right? How does that part of the United States, which is shrinking but still present in rural America, really, you know, write that narrative. And when that narrative gets written too much by coastal elites, like the controversy around the film version of “Hillbilly Elegy,” it doesn’t tend to work so well.

DB: Yeah. The funny thing about “Hillbilly Elegy,” all the critics hated it. It has a Rotten Tomatoes score of 25. The actual people it depicts seem to love it because it has a popular audience score of like 86. Socritics don’t represent America.

I think the election results have shown us how vast the cultural gap is between rural and urban America. And basically what’s happening over the last 40 or 50 years, young, ambitious people have left rural America, for obvious reasons. You know, you go to a town, Wilkes, North Carolina, a small town about an hour outside of Winston-Salem. And they’ll tell you our biggest export here is peopleand a struggle to keep people rooted, and they don’t blame them. There are just no jobs. And Wilkes was the home of NASCAR at one point. It was the home of Holly Field. It was home of some furniture companies. They’re all gone. They all went to Charlotte or wherever. And they’ve got a chicken plant there, but it’s mostly Latinos who work there now. And so there’s just nothing to keep young people there. And there’s even this finding that, you know, we have these Big Five personality traits, people who score high on openness to experience move to New York and do very well in our society. And soI think that that’s part of the new class structure, somehow. The urban–rural, and the geographic concentration of cultural and economic power is just a gigantic driving force between a lot of these new kinds of disparities.

ZK: Ted, why don’t you get the last word.

TJ: I was just going to add very quickly that the answer to that is not to tell people to go to 90-day coding camps, and go from being a coal miner to working at Google. You cannot uproot people and force a hundred percent of the nation to 10 metro areas around the country in search of economic security. We’re going to have to find a way to spread out opportunity and prosperity and not cluster it in particular areas. Because attachment to place is a good characteristic for Americans to have. And we shouldn’t sort of assimilate everyone to metro areas in search of economic opportunity.

ZK: You know, best laid plans of mice and men, I thought we were going to kind of have the funnel go down. We kind of stayed at a big-picture level. But I would say both for Ted and David, you are both intensely people who I feel practice what you preach. You try to see the world through the words that you articulate about how the world is. And David, you’ve made an intensive effort to get out of your own comfort zone to actually find answers, not just in your own mind, but out there. And Ted, you’re, not just your language, although I think the use of language is powerful in your work and in your presence, but also, you know, acting as you preach.

And I think from when I talked about the humility thing, it is a way to really try to make sure that… It’s really easy to think you’re right. It’s really hard to work with other people who also think they’re right and think you’re wrong. And in a noisy, genuinely democratic society, that is the challenge. And that is going to be the task for all of us. And if I could, like, do one thing with The Progress Network and these voices, it’s to say, really just listen, you know, really listen, and not just to yourself speak. And I think both of you have absolutely lived that, and continue to live that. So I salute you. I’m really glad to have had the time with both of you tonight and grateful for Emma for organizing all this, and for helping us try to create a community in The Progress Network. Please, all of you who are listening now and in the future, sign up for our newsletter, spread the word. There’s a slight evangelical quality to this, which I don’t mind owning. And, contact me, contact Emma, contact these guys. And I hope you all have a great solstice a decent, restful, peaceful end to an incredibly unrestful, unpeaceful, unpleasant year. And let’s look to the future and see that we can create a better one. So thank you.

Meet the Hosts

Zachary Karabell