Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

What Could Go Right? Has There Been Any Progress Made on Climate Change Since the Paris Agreement?

Yes. We've made big gains, but we’re still not moving fast enough.

This is our weekly newsletter, What Could Go Right? Sign up here to receive it in your inbox every Thursday at 5am ET. You can read past issues here.

This edition of the newsletter was guest written by Nick Hedley, founder of The Progress Playbook, an online outlet focused on policies and projects that are succeeding in driving sustainable development and could be replicated elsewhere. Today, he takes a birds-eye view of the progress the world has already made in mitigating climate change and how far we have to go.

There will be no edition next week, November 28, as we celebrate Thanksgiving. We’ll be back in your inboxes December 5.

Has There Been Any Progress Made on Climate Change Since the Paris Agreement?

It’s been nearly a decade since world leaders agreed to try and limit global warming to 1.5°C above the pre-industrial era, or 2°C at the very worst. Beyond that level, the risk of irreversible climate tipping points increases dramatically, and the planet as we know it would become almost unrecognizable, scientists warn.

The good news is that we’ve made substantial progress on bending the greenhouse gas emissions curve since the Paris Agreement was signed in 2015.

When that landmark accord was signed, the world was on track to warm by up to 4.8°C by the end of the century, the United Nations (UN) says. That would have rendered large parts of the world uninhabitable and wreaked havoc on food systems and water security everywhere.

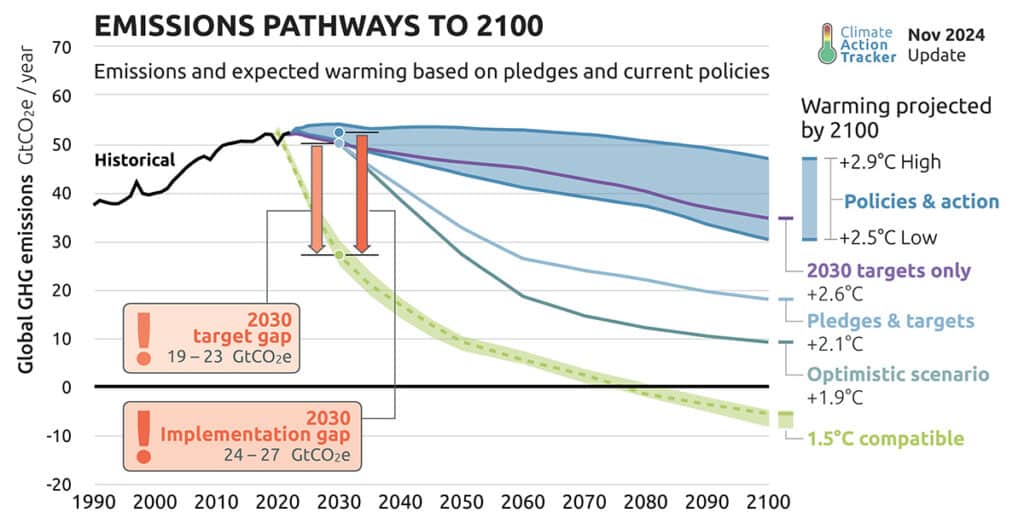

But we are now headed for about 2.7°C of heating, based on current national commitments (which, in any case, are not being met), according to scientists at the Climate Action Tracker project.

Even though that’s still far above “safe” levels, it’s a meaningful improvement in a relatively short space of time, and we now have a fighting chance to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

We’re still setting the wrong kinds of records

This year will almost certainly be the warmest since records began, and likely the hottest in at least 120,000 years, scientists say.

The average surface air temperature is expected to be 1.55°C above pre-industrial levels in 2024—meaning we have already breached the first threshold set out in the Paris Agreement (although the pact refers to long-term averages, usually calculated as an average over 30 years, rather than a single year).

At the same time, carbon dioxide emissions from burning fossil fuels will reach yet another record high in 2024, according to projections from the Global Carbon Project, a research project that establishes a common base of knowledge across the international science community.

Fossil fuel consumption is being driven by rising energy demand, which in turn is largely linked to rapid economic growth and population increases in large developing markets such as India. Electricity use is also being fueled by soaring demand for air conditioning as heatwaves become more frequent and intense, according to the intergovernmental organization International Energy Agency (IEA).

So while many researchers thought we might see peak emissions in 2024, we’ll likely have to wait at least another year to reach this critical milestone. Thereafter, emissions will have to fall sharply every year to keep the goals of the Paris Agreement alive.

It’s widely agreed that limiting warming to 1.5°C is no longer possible, but the upper target of 2°C is achievable if governments ramp up climate action. To meet this goal, emissions must fall 28 percent by 2030 and 37 percent by 2035, relative to 2019 levels, per the UN’s latest emissions gap report.

“There are many signs of positive progress at the country level, and a feeling that a peak in global fossil CO2 emissions is imminent, but the global peak remains elusive,” says Glen Peters of the CICERO Center for International Climate Research in Oslo.

“Climate action is a collective problem, and while gradual emission reductions are occurring in some countries, increases continue in others,” Peters says. “Progress in all countries needs to accelerate fast enough to put global emissions on a downward trajectory toward net zero.”

One of the biggest obstacles to decarbonization, particularly in developing markets, is the lack of funding for clean energy and other critical investments. This is perhaps the most important item on the agenda at the COP29 climate summit in Baku, Azerbaijan.

Recent studies show that developing countries will need at least $1 trillion a year in climate finance in order to meet their net zero goals and adapt to the changing climate.

That’s a tall order, considering that they’re currently receiving only about a tenth of that amount from the Global North.

These nations are showing the way

While some governments are still resisting climate action, others are showing what’s possible with political will and a healthy dose of ambition—even where a dearth of climate finance remains a hurdle.

For example, Chile is phasing out coal faster than any other developing nation due in part to its robust environmental standards, says former environment minister Marcelo Mena-Carrasco.

In the first half of 2024, coal’s share of Chile’s electricity output was 17.5 percent, according to data collated by the research group Ember. That’s down from 43.6 percent in 2016.

Renewables made up 63 percent of the country’s power mix in the first half of the year.

Elsewhere in Latin America, Uruguay’s economy recently ran on 100 percent renewable electricity for 10 straight months, with wind comprising 41 percent of the mix.

And renewables covered more than 90 percent of Brazil’s power requirements in 2023, while low-carbon nuclear accounted for another 2 percent of the total, Ember’s data shows. At COP29, Brazil announced that it would reduce greenhouse gas emissions by between 59 percent and 67 percent by 2035, relative to 2005 levels.

The African nation of Kenya already generates more than 90 percent of its electricity from clean sources, including geothermal power plants, and it plans to reach the 100 percent mark by 2030.

Meanwhile, the state of South Australia, a pioneer of big batteries, currently gets close to three-quarters of its electricity from wind and solar and aims to get to 100 percent net renewables by 2027.

It’s on a similar trajectory to Denmark, which will come very close to the 100 percent renewables mark by the end of the decade, according to the IEA’s forecasts, which show that Portugal isn’t far behind.

When it comes to absolute deployments of clean energy, China is the undisputed leader. The world’s second-largest economy reached its goal of installing 1,200 gigawatts (GW) of wind and solar power generating capacity in July 2024, more than six years ahead of schedule. It’s responsible for nearly half of global installations of the two technologies to date.

China is also rapidly electrifying its transport sector, with electric models now accounting for more than 50 percent of new vehicle sales. That’s helping to curb the world’s thirst for oil, the demand for which is expected to peak within the next few years.

Moreover, China’s deep investments in electric vehicles and other clean energy supply chains have pushed down costs and helped to fuel “a race to the top,” according to a recent report by the nonprofit research group Rocky Mountain Institute (RMI).

The fact that clean technology (cleantech) now outcompetes fossil fuels economically in most parts of the world “will continue to overwhelm a fragile fossil fuel system that wastes two-thirds of its primary energy and fails to pay for its externality costs,” RMI says.

The group’s modeling shows it’s still possible to limit warming to below 2°C above the pre-industrial era, and it sees the Global South largely leapfrogging fossil fuels and going straight to cleantech.

The IEA, meanwhile, thinks the world is nearly on track to meet the COP28 goal of tripling global renewable energy capacity to 11,000 GW by 2030. This means that at the end of the decade, renewables will account for almost half of global electricity generation, from a little over 30 percent today.

Two steps forward, one step back

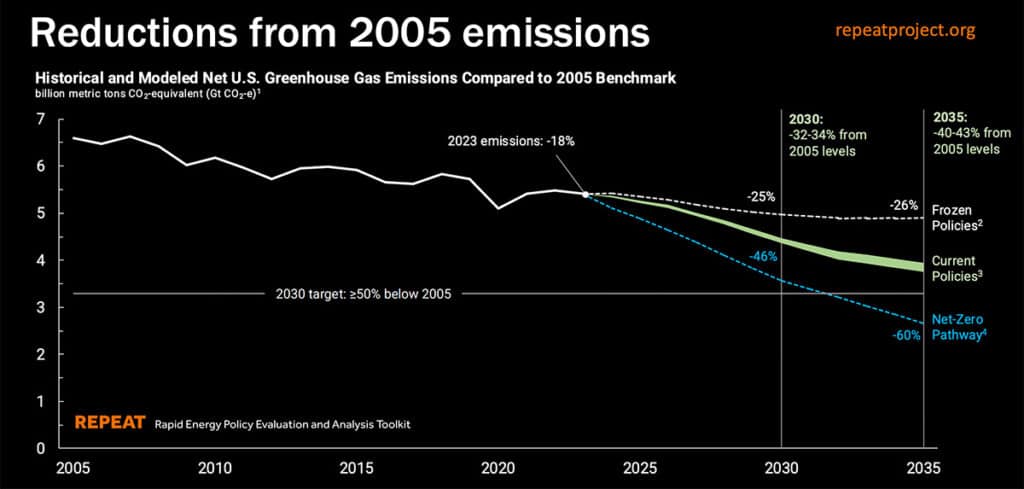

The United States, the second-biggest emitter of greenhouse gasses after China, has made significant progress in reining in emissions over the past few years. That’s partly thanks to the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), which introduced generous subsidies for cleantech manufacturing and adoption.

The legislation helped place the US on track to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by about a third by 2030, relative to 2005 levels, according to modeling by the REPEAT Project, which is led by Princeton University’s ZERO Lab.

However, President-elect Donald Trump, a climate skeptic, has promised to repeal or at least substantially weaken the IRA. His election victory has led to widespread concerns that the country’s decarbonization gains will be reversed.

Provided Trump’s rollback of climate policies doesn’t get replicated in other countries, his return to the White House could add 0.04°C of warming by 2100, according to an analysis by researchers at Climate Action Tracker. That’s more significant than it may sound—but not enough on its own to derail the world’s climate change mitigation efforts.

Moreover, because the vast majority of IRA-linked clean energy manufacturing projects are in rural, Republican districts, there’s now plenty of support for the legislation on both sides of the political spectrum.

In addition, supply chains have become increasingly entrenched, and economics now favor clean energy.

“Climate action is like a giant boulder that’s already reached its tipping point and is now rolling downhill toward a greener future, with millions pushing it,” says atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe.

“It could still be slowed by actions of governments and corporations—delays with serious consequences for people and planet alike—but it can’t be stopped. Gravity, history, and progress are on our side.”

Still, we need to be moving much faster. Based on current policies, emissions will fall just 2.6 percent by 2030, relative to 2009 levels, the UN says. That’s a far cry from the 28 percent drop needed to cap warming at 2°C.

What Could Go Right? S6 E30

How do Americans overcome political polarization? Is not having a monolithic Latino or Black vote good for America? What are some benefits and drawbacks to a Trump presidency? Zachary and Emma speak with Robert Wright, author of Why Buddhism Is True and host of the podcast and newsletter Nonzero. They discuss Trump’s possible impact and strategies, and the potential implications for US relations with China and Iran. | Listen now

By the Numbers

34 x 32: The width and length, in meters, of the world’s largest coral colony, just discovered in the Solomon Islands. It is about the size of two basketball courts and is likely several centuries old.

76%: The share of Americans who have a great deal or fair amount of confidence in scientists to act in the public’s best interests. The rating is still lower than what it was pre-pandemic but has risen instead of dipped for the first time since 2020.

53%: The share of Americans who support the death penalty, the lowest level seen since the 1970s. The decline is generationally split: in contrast to older generations, only 47% of millennials support the death penalty, and 42% of Gen Z.

Quick Hits

🦴 Bone marrow donors, especially for minorities, are hard to find. For the first time, a patient just received a bone marrow transplant from a cadaver, the results of a San Francisco biotech startup’s efforts to create a frozen bank of bone marrow gathered from recently deceased organ donors.

🔞 After 17 years of campaigning and 8 failed attempts to pass legislation through government, Colombia has outlawed child marriage. It becomes the 12th country in Latin America and the Caribbean to ban marriage for minors.

🙅 India’s Supreme Court has banned “bulldozer justice,” in which the home of someone accused of a crime is demolished. It is a tactic deployed by the government in recent years specifically against Muslims, although Hindus have also been targeted.

💉 Cervical cancer could be the first cancer humanity eliminates, writes the director-general of the World Health Organization. He outlines the progress already made and what’s needed to achieve this remarkable goal.

👀 What we’re watching: Last year, a military coup in the central African country of Gabon overthrew the son of the president who had ruled the country for 41 years. Now, voters in Gabon have approved a new constitution that introduces term limits for presidents and bars dynastic succession.

💡 Editor’s pick: How do you sign “carbon footprint”? This article in The Conversation walks you through the process of developing British sign language for twelve abstract climate concepts.

TPN Member Originals

(Who are our Members? Get to know them.)

- If you’re sure how the next four years will play out, I promise: You’re wrong | NYT ($) | Adam Grant

- Trump had it easy the first time | NYT ($) | Thomas L. Friedman

- As threats to our democracy become more tangible, stay grounded in the present | Lucid | Ruth Ben-Ghiat

- Trump’s mass deportation plan | Tangle | Isaac Saul

- How Ivy League admissions broke America | The Atlantic ($) | David Brooks

- Why our election expectations were so wrong | NYT ($) | David Brooks

- Memo to Dems: Don’t blame sexism | Of Boys and Men | Richard. V. Reeves

- The secret to thinking your way out of anxiety | The Atlantic ($) | Arthur C. Brooks

- Our first Trump 2.0 test (and how to pass it) | Nonzero | Robert Wright

- After the election: Swimming in the sea of disinformation. | Breaking the News | James Fallows

- Some hope for AI’s future | WaPo ($) | Bina Venkataraman