Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

Greening the city: pockets of hope for urban biodiversity

Cities are adopting green infrastructure to become more climate-resilient. These measures are reviving all kinds of urban biodiversity as well.

For a long time, biodiversity conservation efforts have focused on national parks, sanctuaries, rainforests, and the like. But our cities are also teeming with rich biodiversity, and they impact the health and quality of life of their residents. “Concrete jungle” notwithstanding, conservation efforts cannot be copy-pasted into urban settings, where biodiversity is severely fragmented. In response, urban planners are reimagining conservation for cities, incorporating infrastructure design measures that both sustain urban wildlife and make cities more climate-resilient.

New York has its bioswales or streetside rain gardens, green patches along pavements that allow rainwater to seep into the ground. In Buenos Aires, living fences purify the air as well as support native plants. Similar solutions across Kuala Lumpur, Mexico City, and Lagos are replenishing urban biodiversity while improving citizens’ lives.

Here are three examples of green infrastructure being taken up by cities across the world. While these examples are specific to the kinds of species present in these cities, the overarching principles are applicable to cities everywhere.

Green roofs in Toronto

The city of Toronto is at the intersection of the Atlantic and the Mississippi flyways, two major routes for migratory birds that make the north-south trip across the Americas. Many bird species such as red-tailed hawks and turkey vultures nest at the many nature reserves in the city. Tommy Thompson park, an artificial peninsula spread over 500 hectares, is home to over 300 bird species, including the largest breeding colony of double-crested cormorants in North America. In recent years, some migrating seagulls have moved their base from this park to green roofs on city buildings, possibly to avoid predators or parasites. Further south on the Atlantic flyway, seagulls are also nesting on green roofs in New York City.

In 2009, Toronto became the first North American city to make it mandatory for new buildings to install green roofs, integrating more natural spaces within the built environment. Such solutions provide a range of ecosystem services, from improvements in air or water quality to preventing floods by keeping stormwater away from the sewers. They are also a way to preserve the shrinking green spaces inside a city. Toronto, for instance, mandated green roofs primarily to tackle urban heat islands. But green infrastructure benefits urban biodiversity as well.

Since roofs are generally underutilized, green roofs are also relatively cost-effective. It’s not as simple, however, as growing any plants that you like in the space available to you. There are considerations to green roof design that maximize their impact, said Dr. Scott MacIvor, an urban ecology researcher at the University of Toronto. His research looks at how the choice of plants to grow on green roofs impacts their performance.

The plant biomass, the soil substrate, and the water the plants retain can make green roofs very heavy. While new buildings are designed with the structural integrity to bear this weight, green roofs on old buildings have limited diversity, as you have to use shallow soils. “Plants grown on shallow soils are also exposed to the roof conditions. So it’s hotter, drier, and windier. All of these extreme conditions mean a limited plant community can be grown, mainly one genus of plants that are succulents,“ Dr. MacIvor told me.

Green roofs with deeper soil substrates, on the contrary, can accommodate different kinds of plants, from succulents to grasses and wildflowers. This variety provides greater water capture, cooling, and shading. And because different plants flower at different times, they consistently attract a greater biodiversity of animals like birds, insects, and bats, and complement urban agriculture practices as the increased number of pollinators benefit from pollination practices on rooftop gardens. They’re also prettier to look at to boot.

Seawalls in Sydney

As sea levels rise, many coastal cities are investing heavily in defensive structures like seawalls and groynes to protect against abnormally high tides or tsunamis. These artificial structures do not provide the kind of microhabitats that can sustain the different species that normally thrive at the interface of land and sea. A more biodiverse alternative is to make these structures mimic those found in nature.

This is the focus of Living Seawalls, a collaboration between researchers at Macquarie University and the University of New South Wales. Dr. Melanie Bishop, a coastal ecologist at Macquarie University and a member of the Living Seawalls project, studies how engineered habitats could conserve biodiversity along the seascape. She stressed that “one of the big problems with these marine-built structures is that they have very smooth and featureless surfaces.”

If you’ve ever walked around shallow tidal pools or on rocky beaches, you would have noticed a rich diversity of stones, corals, and other kinds of intricate stuff. These have innumerable nooks and crannies where crabs, urchins, snails, and other animals hide. In many parts of the world, mangroves or kelp forests serve the same purpose. Because “the place that all the marine life lives is actually those hidey holes” and built structures lack these, they do not support the kind of biodiversity that natural habitats do.

Living seawalls include carefully designed holes that fill this gap. With different types of holes, they provide different types of habitats that allow organisms with very different requirements to live alongside each other. The choice of holes to add also depends on the ecosystem services that you want to obtain from the living seawall panels.

To this end, the Living Seawalls project offers organizations to install these seawalls at their sites. “If the key goal is the improvement of water quality, we suggest panels that increase the abundance of oysters and mussels that clean the water through their filter-feeding,” Dr. Bishop explained. “If the key goal is to enhance fisheries productivity, then we would recommend panels that we know target key prey species of those fish or provide hiding holes for juvenile fishes.”

One of the first installations was done at the Sydney Harbor. Here, over two years, the artificial sewalls were populated by oysters, barnacles, and seaweed. These, in turn, attracted fish like bream for recreational fishing. Another installation is at the Sawmillers Reserve and Bradfield Park, a nature reserve in North Sydney. Within a few weeks, they were teeming with a diverse marine community, including snails and limpets among other species.

Coastal regions are witnessing what Dr. Bishop called “a construction boom in the oceans.” There are a lot of new structures that support intense shipping operations, recreational facilities, aquaculture systems, and offshore renewable energy installations. These also provide new opportunities to install these living panels to further boost marine biodiversity.

Switching off the lights in France

A major determinant of urban impact on biodiversity, something that some species are already evolving in response to, is artificial light at night (ALAN). Nocturnal animals are not used to living and moving around in the presence of such harsh light as is emitted by streetlights and billboards. Not only does ALAN disturb the circadian rhythm of plant and animal species, but it also fragments their habitats into patches of relative darkness interspersed with a lot of light.

Seen as skyglow even kilometers away from urban centers, ALAN doesn’t just hurt nocturnal wildlife in the cities, but even around them. To tackle the adverse impact of light pollution on urban wildlife, many researchers are advocating for the greater adoption of dark infrastructure. In simpler words: switch the lights off. In more practical terms, dark infrastructure refers to interventions that lower the use and intensity of ALAN.

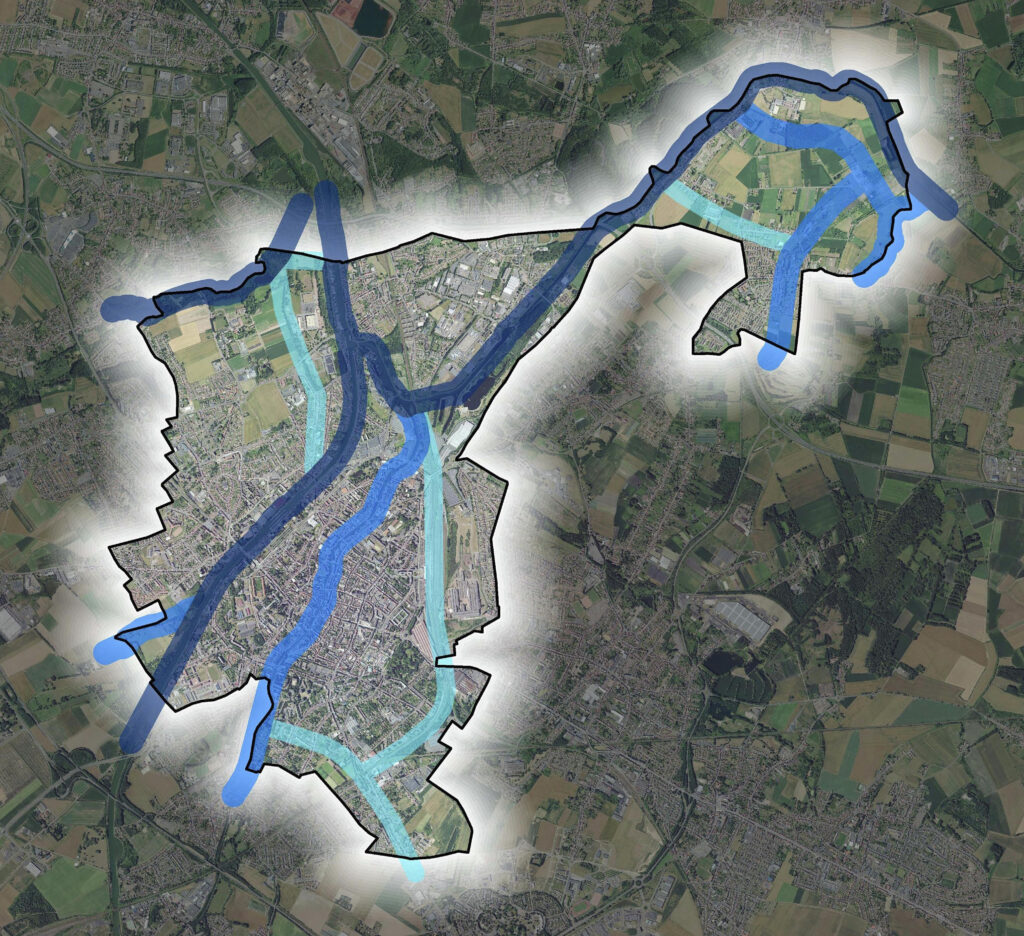

For example, in the French town of Daoui, researchers created a bat activity map by recording the bats’ activity in different regions. Then, they implemented dark infrastructure from scratch by drawing up routes with differing levels of darkness. Even if switching off the lights across a city isn’t a viable solution, evidence-based approaches to implementing dimming measures can help.

In fact, the term dark, instead of black, implies that varying degrees of darkness should be implemented. For instance, street lighting that dims in response to the traffic or using warmer colors are easy-to-implement interventions that significantly improve the conditions for nocturnal wildlife. Dr. Janine Bolliger, a landscape ecologist at the Swiss Federal Institute for Forest, Snow and Landscape Research, investigates the effectiveness of these interventions on nocturnal biodiversity.

“Some bats are indifferent to the light conditions. Others are not observed at the light [sources], even if we dim the light,” Dr. Bolliger told me. This hints that artificial night is reducing bat diversity. The dark infrastructure supports both kinds of bats. For insects, harsh lights are almost always detrimental as insects are fatally attracted to light sources.

Cities are coming up with creative measures to identify and protect dark corridors for the movement of nocturnal species. For example, a team of researchers mapped the regions for dark infrastructure in Geneva by comparing low ALAN areas with existing green infrastructure. Another group of US-based researchers used satellite mapping to identify similar regions in Los Angeles. Even when the extent of light pollution prohibits a continuum of dark infrastructure, such measures are a good start. Even though the Daoui research mapped transitory pockets of darkness, it guides researchers to take measures that restore dark infrastructure to restore and maintain continuous corridors.

Green cities are livable cities

By 2050, two in every three people around the world will live in cities. For most of them, urban biodiversity will be their primary contact with any form of wildlife. And as the global urban land area grows and biodiversity elsewhere declines, cities will be home to a greater share of the global biodiversity. For these reasons, it’s crucial to take measures that conserve this biodiversity—plus, city authorities will be happy knowing that green infrastructure strategies come hand-in-hand with such benefits as lower energy bills and flood prevention.

Green infrastructure does not fully compensate for the biodiversity loss when a new urban area comes at the site of a forest or a marshland. However, any amount of green infrastructure is more biodiverse than the concrete jungles that many cities today are. This is why the wider adoption of green infrastructure in urban planning will be critical to making future cities more livable.