Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

What Could Go Right? The Eradication of Guinea Worm Disease Is Close

2024 may be the first year with under 10 human cases.

This is our weekly newsletter, What Could Go Right? Sign up here to receive it in your inbox every Thursday at 5am ET. You can read past issues here.

The Eradication of Guinea Worm Disease Is Close

In all of human history, we have eradicated two diseases—smallpox, in 1980, and rinderpest, in 2011. We are now on the cusp of eradicating a third: guinea worm.

In the 1940s, there were an estimated 48 million annual cases of guinea worm disease worldwide. Improved sanitation brought that number down significantly over the decades. By 1986, when international health bodies, along with the humanitarian organization The Carter Center, revved up eradication efforts, there were an estimated 3.5 million cases per year.

People become afflicted with guinea worm disease by drinking contaminated water that contains the worm’s larvae. The larvae then mature inside the human body, wriggling through “connective tissue, joints, and bones,” write Saloni Dattani and Fiona Spooner for Our World in Data, causing arthritic conditions. After about a year, the adult worm slowly emerges through the skin and, when it comes in contact with water, releases new larvae.

Guinea worm disease has been with us for a long time. “The disease is mentioned in Egyptian medical texts dating to 1,550 BC,” writes Sarah DeWeerdt in Nature, “which also describe the treatment that is still standard today: winding the emerging worm around a small stick and painstakingly pulling it out centimeter by centimeter over the course of weeks.” By the time a guinea worm pokes itself out of the body, it can be up to three feet (one meter) long. It’s crucial that the worm not break during the extraction process, as it can create a secondary infection.

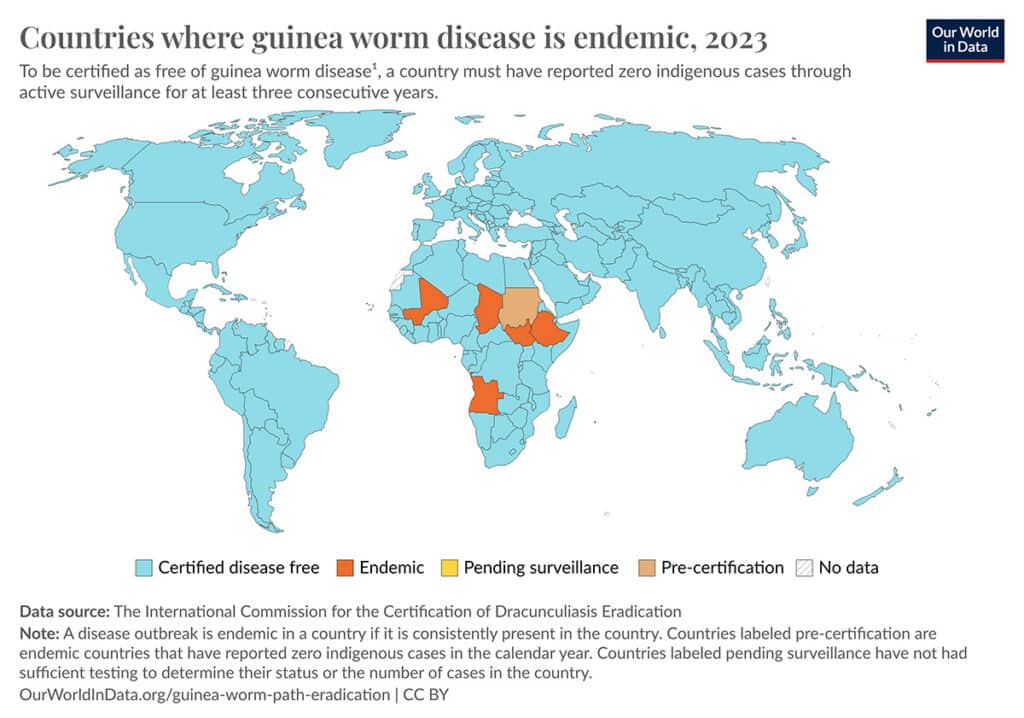

Guinea worm disease used to be widespread across 20 countries in Africa and Asia. Today, it is endemic in only five—Angola, Chad, Ethiopia, Mali, and South Sudan—and case numbers have been dwindling over the past few years. There were 54 reported human cases in 2019, 27 in 2020, and 14 in 2023.

There is no drug or vaccine for guinea worm. All of the progress that has already been made has been through fairly simple, bottom-up efforts, such as filters and straws for drinking water and the conscription of community volunteers who surveil cases and help care for and educate patients.

Early this year, there was some excitement that 2024 would be the first year with zero human cases, when none had been reported through April. But in May, one cropped up in Chad. Countries must see zero cases in both humans and animals for three consecutive years to be declared guinea worm-free. Eradication, the public health certification after elimination, would occur when intervention measures are no longer necessary.

Still, the next few months will indicate whether 2024 will be the first year in human history with fewer than 10 human cases or not.

If there is something that will prevent guinea worm’s eradication, it is animal infections. They already delayed the target set for eradication from 2020 to 2030, when scientists realized around 2012 that guinea worms were infecting new animal hosts like domestic dogs and cats, and even donkeys and baboons. The public health community is now working to limit guinea worm’s spread in animals; annual cases number in the hundreds and are mostly in Chad.

One positive sign is that animal infections have been dropping off the past few years. In Chad, total cases (animal and human, but animal are most of the tally) have gone from 4,331 in 2019 to 899 in 2023. This year is also so far, so good: animal infections have declined 37 percent in the first five months of 2024 as compared to 2023.

Based on that general rate of decline, a more realistic timeline for eradication is probably a touch beyond 2030, although that statement enters the realm of guesswork and ill-advised fortune-telling. There is no guarantee that eradication will happen in the next decade or ever. But we are tantalizingly close.

What Could Go Right? S6 E15

Can anyone truly read a poker face? Join Zachary and Emma as they speak with Maria Konnikova, who takes us on her journey from earning a PhD in psychology to becoming a professional poker player. Maria sheds light on the gender disparities within poker, detailing the unique challenges women face in this male-dominated arena and sharing her triumphs that have garnered her respect and recognition beyond the poker table. Beyond the cards, Maria’s fascination with the darker aspects of human behavior leads her to explore con artists and the psychology of cheating. | Listen now

By the Numbers

71%: The drop in teen birth rates in the US between 2000 and 2022

40%: The global decline in the number of children not attending school since 2000

2.45M: The number of Filipinos lifted out of poverty since 2021

Quick Hits

🕵️ The viral study that found that there are heavy metals in tampons is misleading, writes a science communication fact checker. “The levels of lead in the tampons were so low that even if you ate dozens of tampons, you’d still probably not be able to absorb enough of the metal to harm you.”

🩸 A new array of blood tests may help doctors diagnose Alzheimer’s disease faster and more accurately in the future, without a brain scan or spinal tap. Some of the tests are more trustworthy than others, however, and doctors are waiting for guidelines from bodies like The Alzheimer’s Association and the FDA.

📉 UNAIDS has just released new global data on HIV and AIDS. Since 2010, there has been a 39 percent drop in new HIV infections, and AIDS-related deaths are down 51 percent; the progress is concentrated in sub-Saharan Africa, however. Meanwhile, two fresh cases of patients in full remission of HIV infection have given scientists clues for a potential cure that may not involve a bone marrow transplant, and a new, twice-yearly injection has been 100 percent effective in preventing infections in women.

🌎 Many climate organizations believe that we are about to arrive, or perhaps have already arrived, at the global peak of carbon emissions. The start of 2024 is promising. The Carbon Monitor Project found that emissions between February and May of this year were slightly lower than over the same period last year.

🇿🇦 South Africa, a top greenhouse gas emitter and with a new government at its helm after general elections in May, passed its first sweeping climate change law, which aims to bring the country within the reductions set by the Paris Agreement to limit global warming.

🐯 Canadian conservation authorities have declared the narwhal—with its spiraled tusk, the unicorn of whales—no longer at risk, since its population is stable despite threats. The report for the 11 other species that were assessed simultaneously, however, was mixed. And in Thailand, tiger populations have doubled over the past two decades.

💡 Editor’s pick: Sarah Constantin takes a look at the future of reproduction, from artificial wombs to genetic screening to extending fertility, and assesses each development’s status and rate of progress. Those becoming pregnant in the 2040s–2060s, she writes, are likely to have a wider set of possibilities.

TPN Member Originals

(Who are our Members? Get to know them.)

- The surrender of the gods, part 1 | The Roots of Progress | Jason Crawford

- 🎧 Can religion make you happy? | The Atlantic ($) | Arthur C. Brooks

- Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s five principles of personal freedom | The Atlantic ($) | Arthur C. Brooks

- No, young men are not turning away from gender equality | Of Boys and Men | Richard V. Reeves

- The new global wave of anti-authoritarianism | Lucid | Ruth Ben-Ghiat

- This was a good US GDP report! | Faster, Please! | James Pethokoukis

- We’re asking the wrong question about Harris and race | NYT ($) | John McWhorter

- Everything you need to know about Kamala Harris, part 1 | Tangle | Isaac Saul

- Kamala’s very good foreign policy guy | Nonzero | Robert Wright

- A good week for democracy | The Edgy Optimist | Zachary Karabell

- Mark Cuban’s company can help rectify America’s drug shortages | STAT | Ezekiel J. Emanuel

- Kamala Harris should shake the Etch-A-Sketch | Slow Boring | Matthew Yglesias

- Who is Tim Walz? | Breaking the News | James Fallows

[…] In all of human historical past, we’ve eradicated two illnesses—smallpox, in 1980, and rinderpest, in 2011. We are actually on the cusp of eradicating a 3rd: guinea worm. […]