Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

What Could Go Right? 275M Previously Undiscovered DNA Variants

A federal health project is adding to our trove of knowledge on the human genome.

This is our weekly newsletter, What Could Go Right? Sign up here to receive it in your inbox every Thursday at 5am ET. You can read past issues here.

275M Previously Undiscovered DNA Variants

Last week, a federal public health endeavor many have never heard of released a wealth of data—275 million previously undiscovered DNA variants, found in the genome sequences of 250,000 Americans who had volunteered to help advance biomedical research. Half of them were racial and ethnic minorities.

The National Institutes of Health’s (NIH) All of Us program, which aims to gather genetic data from one million Americans by 2026, is unprecedented in its diversity and scale. Their latest release is a significant addition to a pool of genomic data that has been overly drawn from participants of European ancestry, a step toward ensuring that precision medicine will be an innovation beneficial to everyone, and a rare sign of trust between the public and government health agencies.

What is precision medicine?

Scientists, researchers, drug companies, and governments have been chasing the dream of precision medicine for at least two decades. Rather than a “one size fits all” approach to medical care, precision medicine is tailored to each individual. It takes into account not only a patient’s lifestyle and environment but also their genetic makeup, or the genetic profile of their illness.

Imagine genetic testing being a routine component of medical care, so you could know if you are at higher risk for Alzheimer’s disease or specific types of cancer, detect a rare disease before symptoms begin, or target a malignant tumor with a drug specifically developed for that mutation.

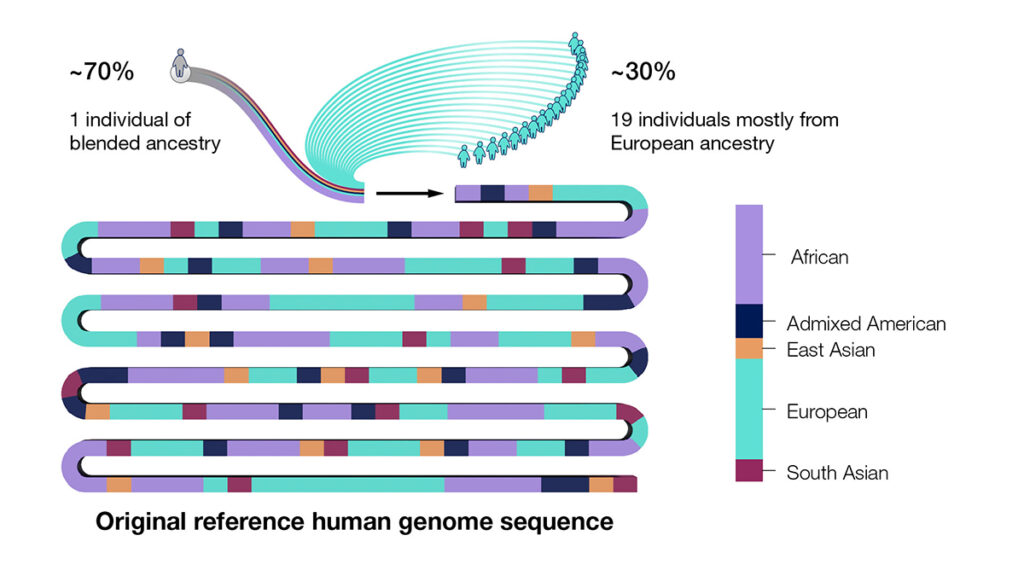

These are all examples of tools that have already been developed thanks to our progressively increasing knowledge of the human genome. The genome was mapped for the first time in 2003, updated in 2022 in order to fix mistakes and fill in gaps, and is still being worked on. That map is based on DNA from just a few donors from Buffalo, New York.

With genomic data, more is more

The ability to fully sequence a genome set the stage. One isn’t nearly enough, however, for precision medicine to flourish. For that, data as comprehensive as possible is needed; ideally, the data would reflect the full genetic diversity of the world, enabling scientists to study rare genetic variants as well as links between genetic markers for disease and populations from different parts of the globe.

The majority of data used to find these links, however, come “from people living in just three countries—the United Kingdom, the United States, and Iceland,” reports STAT News. Of the 500,000 volunteers participating in the UK Biobank’s genome-sequencing dataset, among the world’s largest, 88 percent are white.

That is a somewhat sensible figure for England and Wales, which are over 80 percent white, but of limited use elsewhere, including in the highly diverse US. Genetic variations that suggest disease risk can appear more frequently in some ethnic groups than others or are sometimes completely absent. Ethnic groups may also have a variant that protects against disease. These variations cannot be caught without a fully representative dataset.

All of Us is a fresh approach

All of Us set out from the start to avoid the trap of unrepresentative data. That involves, however, gathering extensive health records, not to mention blood, spit, and urine, from communities historically distrustful of federal health agencies, and within the US’ massive, unwieldy health system. When national enrollment began in 2018, All of Us CEO Josh Denny told Stat News that the program researchers weren’t sure if the plan was even executable.

Six years in, more than 750,000 Americans have participated, 77 percent of them from communities that are historically under-represented in biomedical research and 46 percent from under-represented racial and ethnic minorities, write the All of Us investigators in a paper published in Nature.

Another thing All of Us does differently is make their work easily accessible. Summary-level data is publicly available, and individual-level data is open to participating institutions as long as researchers complete a course on its ethical use. The volunteers can also opt in to receive their DNA results, including genetic ancestry and hereditary disease risk. In this latest dataset, All of Us researchers found genetic markers correlating to height, cholesterol, type 2 diabetes, coronary artery disease, and atrial fibrillation (when the heart beats irregularly).

The story of precision medicine is going to be one that continues to evolve over the next few decades. For now, it’s a welcome break to hear about the US government doing good public health work—not because it doesn’t happen, but because it doesn’t as easily reach our eyeballs and ears.

By the Numbers

18.7%: The share of seats in Togo’s national parliament held by women in 2022, up from 1.2 percent in 1997.

25: The percent of lawmakers in the US’ 118th Congress who identify as black, Hispanic, Asian American, American Indian, Alaska Native, or multiracial, up from about 15 percent in 2009. Just over 40 percent of the American population identifies as non-white.

63%: The homeownership rate of Asian Americans, up from 57 percent in 2012. The share of Hispanic, black, Asian American, and white homeowners all grew in the last decade.

Quick Hits

🌲 Do you live in the US’ “warming hole,” parts of the southeast where temperatures have flatlined or cooled despite global warming trends? A new study says that a century’s worth of reforestation is playing a major role.

🐘 Bangladesh has halted the licensing of elephant ownership, where critically endangered elephants have often been used for begging, circus tricks, and hauling logs. Adoption of these elephants is now banned.

🧠 A 13-year-old boy from Belgium has been cured of a rare, deadly brain cancer for the first time. His case offers a potential pathway for the development of drugs that would cure other affected children.

🏠 Seoul’s city government has taken the unusual step of providing rental support to single people, with single households nearing 40 percent of the city’s population. The government is encouraging new construction of rental units that will be offered at up to 50 percent less than market rates. (Bloomberg $)

👶 A vaccine for RSV, which can be deadly for babies and the elderly, was approved for the first time in the US last year. Uptake so far has been promising: more than half of US newborns are now protected.

⚖️ Last year, three states banned utility companies from charging customers for political lobbying, advertising, and other associated activities. Now eight more have legislation in the works.

👪 In a suburb of Tokyo, pro-childcare policies have resulted in an increasing birth rate, unlike in the rest of the country. Additional daycares, and transport to and from them, have made the difference. (Bloomberg $)

👀 What we’re watching: We’ve written about how the death penalty in the US, in practice, is waning. Conservatives and religious groups in Oklahoma, one of the only states to carry out executions last year, are reigniting the debate.

💡 Editor’s pick: Is AI really thinking, or just good at regurgitating facts? One Substacker fed bots IQ tests, and was surprised by the results.

TPN Member Originals

(Who are our Members? Get to know them.)

- The US’ missed opportunity in Latin America | Foreign Affairs ($) | Shannon K. O’Neil

- Can Ukraine win the war? | GZERO | Ian Bremmer

- “A thieving little man in his bunker”: Lessons from the life and work of Navalny on resisting autocracy | Lucid | Ruth Ben-Ghiat

- How to protect elections in the age of AI | GZERO | Ian Bremmer

- Why Iran is pulling back from the brink | GZERO | Ian Bremmer

- The Trump fraud ruling | Tangle | Isaac Saul

- The arrest of the Biden informant | Tangle | Isaac Saul

- The political failure of Bidenomics | NYT ($) | David Brooks

- Election countdown: The new politics of place | Breaking the News | James Fallows

- Will you join the supermajority for constitutional democracy? | WaPo ($) | Danielle Allen

- US media is collapsing. Here’s how to save it. | Jacobin | Alissa Quart

- Florida Man!: How a regional Florida newspaper informs its citizens and encourages activism | Our Towns | Deborah Fallows

- How a playwright became one of the most incisive social critics of our time | The Atlantic ($) | Thomas Chatterton Williams

- Four ways to quit complaining | The Atlantic ($) | Arthur C. Brooks

- Why you, personally, should want a larger human population | The Roots of Progress | Jason Crawford

- Biden’s tough love deficit | Nonzero | Robert Wright

- America finally returns to the Moon | Faster, Please! | James Pethokoukis

- Marshall McLuhan on why content moderation is a red herring | After Babel | Jonathan Haidt