Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

What Could Go Right? How the Philippines Is Slashing Poverty

The Southeast Asian nation is doing the most to get their poverty rate into the single digits.

This is our weekly newsletter, What Could Go Right? Sign up here to receive it in your inbox every Thursday at 5am ET. You can read past issues here.

How the Philippines Is Slashing Poverty

In our By the Numbers section last week, we shared an impressive statistic: 2.45 million Filipinos have been lifted out of poverty since 2021. One of our fantastic readers wrote in and asked how this happened. How could a country move that many people out of poverty so fast?

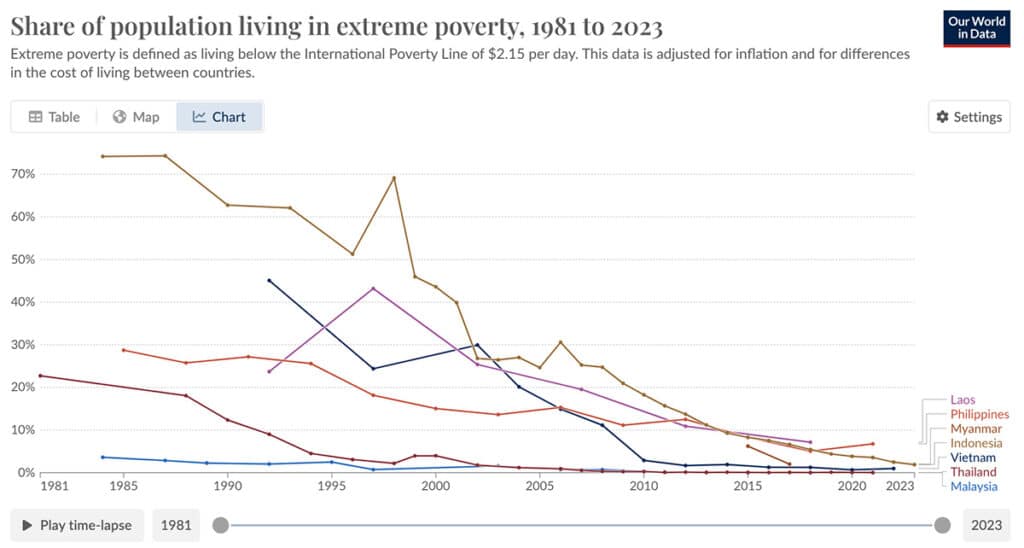

It happens all the time. You wouldn’t know it by reading news headlines, but over the past four decades or so, Southeast Asia has been busy transforming itself. When it comes to poverty reduction, the Philippines is actually a laggard compared to many of its neighbors, which have all but eliminated extreme poverty, defined in the chart below as living on less than $2.15 per day.

So while the focus today is on the Philippines, an even better success story—broadly speaking—could also be written about Malaysia, Thailand, Indonesia, or Vietnam. Myanmar would have been in that group as well if a military takeover in 2021 hadn’t sent them reeling backward.

The Philippines has been reaching for upper middle-income status for some time, and is trying to get there by 2025. They also have a goal to reduce poverty rates to single digits by 2028. That rate is not for extreme poverty, defined by using international guidelines, as shown above. It’s poverty as the Philippines has defined it nationally, which is the average amount that would cover a person’s basic needs. For 2023, that was set at around $575 per year.

While setbacks due to the pandemic were covered by the media, it’s almost impossible to find coverage about how quickly, post-Covid, the Philippines reversed the reversal. In late July, the Philippine Statistic Authority announced the 2023 poverty rate: 15.5 percent, which makes up for ground lost during the pandemic and then some. That means millions have indeed been lifted out of poverty, but 17.5 million are still mired in it.

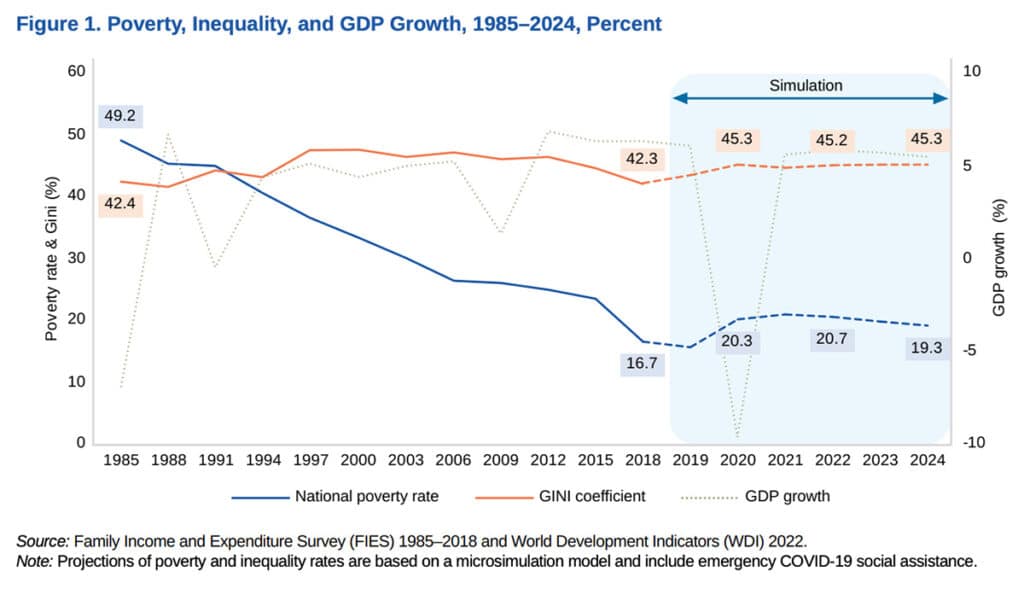

Zooming in on the unusual pandemic years, however, obscures just how far the Philippines has come. The poverty rate in 1985 was 49.2 percent.

How did they do it?

They grew the economy. As the Filipino economy moved from agriculture- to industry-based, GDP has been growing since the 80s, although not always steadily. It wasn’t until after the millennium, however, that growth began benefiting the poor. More recently, the government has touted spending on big infrastructure projects as a job creation mechanism as well as grants and affordable loans for small- to medium-sized businesses.

They expanded secondary education. The government has been pushing access to middle and high school education through various means. One is a cash transfer program that awards poor families who send their kids to school with a few hundred dollars per year. While the program could be targeted better, education rates, even among the poorest, have risen, leading to higher-paying jobs and financial security.

Expanding access to tertiary education is next. Certain university-level programs are free to attend, but experts say that those efforts are not reaching the poor.

They rolled out a national health program with automatic enrollment in order to create a safety net for those bankrupted by illness. They have nowhere near achieved universal coverage, however.

They instituted tax reform. Since 2018, those earning under about $4,300 per year do not pay income tax. While over time the government has increased VAT rates and what gets taxed, there are exemptions that benefit the poor (for instance on certain food products and educational and health services), and the government has increased taxes on cars, tobacco, and oil to pay for spending.

They recovered quickly post-pandemic. Poverty progress during Covid went backward. At the time, the World Bank expected a slow, uneven economic recovery, but the Philippines has instead bounced back quickly, with GDP growth rates outpacing many other nations. That has affected expectations about the poverty rate, too, as illustrated below.

To help the poor, there was a two-month cash program for the unemployed during the pandemic. Many other one-time subsidies, like for rice or free commutes, were enacted post-pandemic to take the sting out of inflation. Tariffs were also lowered on basic foodstuffs while inflation remained high.

Those are just a few of the top-line efforts that have made the difference. Not everything has worked perfectly or at all. Half of those still living in poverty are agricultural workers; a previous agrarian reform actually worsened their lot by breaking up land ownership. And more can be done to protect farmers against natural disasters, which are common.

This is one of those stories, though, that progress advocates regard, and for good reason, as under-told.

What Could Go Right? S6 E16

Should psychedelics be legal nationwide? Are they a bipartisan topic? And if they become a retail product like marijuana, how would screening and licensing work? Join Zachary and Emma as they speak with Oshan Jarow, a staff writer at Vox’s Future Perfect. Oshan discusses psychedelics in politics, cultures using these drugs therapeutically and spiritually, and both the controversial history and legal future of psychedelics. | Listen now

By the Numbers

96%: The decline in malaria deaths in Bangladesh between 2008 and 2023. The country is gunning for zero deaths by 2027, although it’s questionable whether that will be achieved.

62%: The drop in use of prescription opioids since its peak in 2011. (More on this in the coming weeks.)

11: The number of states, plus DC, that have enacted pay transparency laws, which can require an employer to disclose salary ranges for open positions.

Quick Hits

🥜 Australia, the “allergy capital of the world,” is the first to offer a national program for babies with a peanut allergy. The treatment regime gradually builds immunity to the allergy with daily exposure to a peanut powder.

📉 In terms of inflation, the world is not completely back to pre-Covid reality, but it’s close. The median inflation rate is now 2.9 percent, after hitting a high of 9.4 percent in July 2022. “An array of forces are now in place to lower global inflation in the coming months,” says the World Bank.

🌪️ New, superfast AI-powered models—which can run on desktop computers instead of on the “room-size supercomputers” that are the current standard—are helping to evolve weather forecasting, sometimes making it more precise. Especially with severe weather, better forecasting can save lives. (NYT $)

🌞 The International Energy Agency is predicting that renewables will overtake coal as the world’s leading source of power generation next year.

🐦⬛ Ten years after advocacy groups intervened, tricolored blackbirds, driven to near-extinction by dairy producers whose harvests would destroy the birds’ nests, are bouncing back. What worked was a simple payment to farmers to delay their harvest until after the chicks had fledged.

🗳️ The Federal Communications Commission is proposing a rule that would mandate disclosure of AI-generated content in political ads. While it may not become active before the presidential election, about half of states have already passed (bipartisan) legislation aimed at regulating deepfakes in elections.

🌎 New United Nations projections say that global population numbers will peak earlier, in the mid- 2080s, and fall to lower levels than previously predicted. Officials say this is a positive development insofar as it suggests reduced pressure on the environment.

👀 What we’re watching: Two countries are embroiled in people-led fights for democracy. In Venezuela, strongman Nicolás Maduro is not showing any signs of stepping down despite strong evidence that he stole a recent election. In Bangladesh, weeks of student protests evolved into an effort to oust the prime minister, Sheikh Hasina, after hundreds of protestors were killed. Hasina has fled the country, protestors have declared victory, and an interim leader has been appointed. The mood is jubilant but jittery, as Bangladeshis wait for the situation to settle.

💡 Editor’s pick: When a gender controversy is not even from Russian disinformation, but a single, corrupt Russian official. Jeremiah Johnson digs into the attention surrounding Algerian Olympic boxer Imane Khelif. Plus: Reuters has a fun graphic novel-style explanation of how the ancient Olympics were run.

TPN Member Originals

(Who are our Members? Get to know them.)

- The importance of government R&D: A quick Q&A with economist Andrew Fieldhouse | Faster, Please! | James Pethokoukis

- Biden proposes major Supreme Court reforms | Tangle | Isaac Saul

- The election in Venezuela, explained | Tangle | Isaac Saul

- The either-or economy | The Edgy Optimist | Zachary Karabell

- Would Trump stop free and fair elections? Hitler and Mussolini’s paths could be a clue | LA Times | Ruth Ben-Ghiat

- How to fix presidential primaries | Slow Boring | Matthew Yglesias

- AI’s benefits outweigh the risks | NYT ($) | David Brooks

- Why you shouldn’t follow the crowd | The Atlantic ($) | Arthur C. Brooks

- Identity politics loses its power | The Atlantic ($) | Thomas Chatterton Williams

- Trump’s outreach to Black men hits a stumbling block: Kamala Harris | WaPo ($) | Theodore R. Johnson

- What Trump means when he mispronounces ‘Kamala’ | NYT ($) | John McWhorter

- America may soon face a fateful choice about Iran | NYT ($) | Thomas L. Friedman

- The Haniyeh assassination will haunt Israel | Nonzero | Robert Wright

- 🎧 An interview with Argentina’s radical new president, Javier Milei | GZERO | Ian Bremmer