Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

Should I buy an electric car?

You asked, we answered.

Amid all the climate news in the United States and the market reaching the tipping point for mass adoption of electric vehicles (EVs), one newsletter reader wrote in with some great questions and valid concerns about what someone should know before buying an EV. We dive into it below.

1. Where do electric vehicle batteries and components come from? Are there issues with unfair labor practices in these places?

The short answer: Most EV batteries come from China, with much of the world’s cobalt—a key component of the lithium-ion batteries that most EVs use—coming from the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), where child labor and unfair labor practices are an issue.

Details: China produces around three-quarters of the world’s lithium-ion batteries. The country also dominates other aspects of the EV battery supply chain, including mining operations in Australia, Chile, and the DRC.

Chinese companies control nearly 70 percent of the mining sector in the DRC, which supplied around 70 percent of the world’s cobalt in 2021. Unfair labor practices linked to cobalt mining, including child labor abuses, have been well documented in the DRC. There have also been reports of forced labor in the EV battery supply chain within China.

Looking ahead: The majority of the global supply chain is likely to stay with China through the end of the decade, according to a 2022 report by the International Energy Agency, but governments in Europe and the US are taking steps to develop their domestic battery supply chains.

In the US, for example, the recently passed Inflation Reduction Act includes billions in manufacturing tax credits aimed at driving US automakers toward, as Axios puts it, “a rapid build-out of manufacturing capacity for electric vehicles, batteries, and the components and materials required to produce them.” Likewise, the infrastructure law passed last year, The New York Times reports, “devoted $7 billion to developing the domestic supply chain for critical minerals.”

That is not a panacea for the serious mining challenges that remain. Major obstacles exist even domestically, but there is no shortage of work being done to overcome those obstacles and make battery production more sustainable, as mineral mining has its own negative environmental impacts. Time will tell how the many ongoing EV battery advancements—like the development of lithium-ion batteries that use more sustainable materials, solid-state batteries that are smaller and lighter, and aluminum-sulfur batteries that provide low-cost storage for renewable sources—play out. But the encouraging signs are plentiful.

2. Do EVs really have a lower carbon footprint than combustion cars? What about manufacturing and charging emissions?

The short answer: Yes, over their full life cycle, EVs have a lower carbon footprint than gas cars. But there are a lot of interconnecting parts.

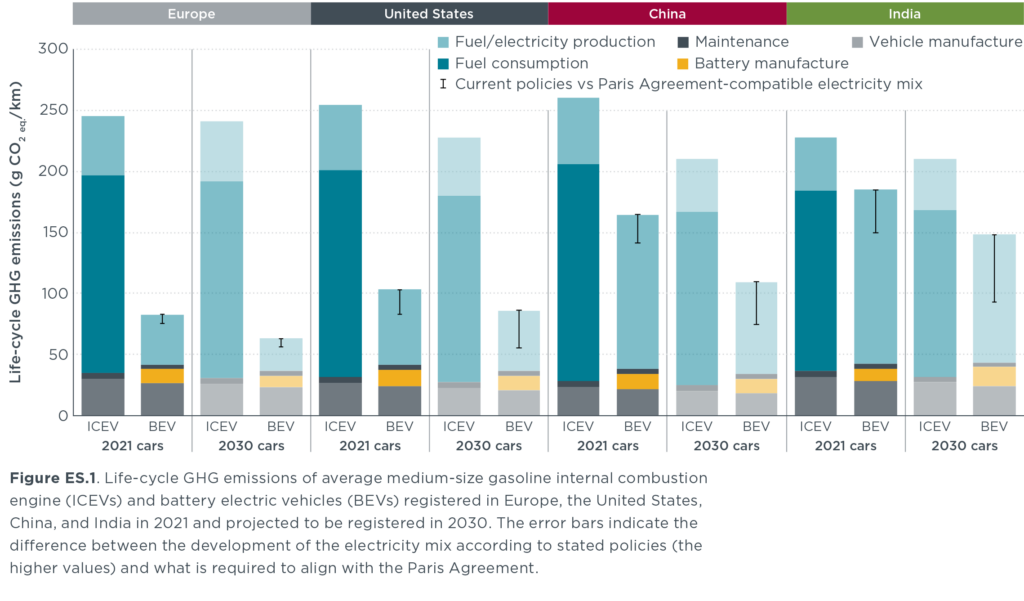

Details: Studies have found that CO2 emissions from manufacturing EVs are higher than from making combustion automobiles (60 percent higher in one study in China, according to the Financial Times). This is largely the result of the various stages of battery production, which account for over a third of the CO2 emitted during the production of an EV. However, those emissions are offset over time by EVs’ superior energy efficiency.

Battery-charging emissions are still a factor, though, especially as most of the world’s electricity grids are still being powered by fossil fuels. Still, even with today’s power plants supplying the energy, total emissions from EVs across their entire life cycle—including the mining and manufacturing processes—are lower than those of combustion vehicles. How much lower? Potentially a lot, depending on location.

In countries where much of the grid runs on renewables, life cycle charging emissions are reduced substantially. In countries powered largely by coal, the reductions, while still significant, are less. In a 2021 study, for example, the International Council on Clean Transportation estimated that life cycle emissions from an EV are 66-69 percent lower than gas cars in Europe, 60-68 percent lower in the US, 37-45 percent lower in China, and 19-34 percent lower in India.

Looking ahead: As the world continues to shift to more renewable energy sources, EVs’ already relatively low carbon footprint is expected to keep getting lower. Manufacturing and technological advancements are likely to help that process along.

3. What happens to old EV batteries? Can they be recycled? Affordably?

The short answer: Currently, EV battery recycling is pretty weak and expensive, but there are promising developments on the horizon.

Details: Precise figures for what percentage of lithium-ion batteries are recycled are hard to come by, but the number often quoted is around 5%. At the moment, recycling’s simply not cost-effective.

Battery replacement is not an affordable option for everyone, either. While the cost varies, it can run anywhere from a low of around $2,500 to a high of around $20,000. Looking at a vehicle like the Chevy Bolt, which is one of the more popular EVs sold in the US, replacing the battery would cost around $9,000. That’s all assuming that the vehicle is no longer under warranty. In the US, though, all EV batteries are guaranteed under warranties for 8 years or 100,000 miles of use.

Under current estimates, most EV batteries will last between 10 and 20 years. Though it’s worth noting that some batteries are lasting longer than predicted, up to or beyond the 20-year mark, and even outlasting the vehicles they were installed in.

On the recycling front, the prospect of millions of batteries heading to landfills obviously poses a challenge. It also presents an opportunity for companies and consumers to benefit from a “circular economy” in which batteries are affordably and profitably recycled. We’re not there yet. But we are moving in that direction. And getting there would be a boon for companies, EV drivers, and the environment.

Looking ahead: A number of startups and partnerships are already working on both recycling and reusing the materials from old batteries. Automakers are now even using retired batteries to build large-scale energy storage. These are but a handful of the many efforts underway.

This team in a lab outside Chicago, for example, is part of a nationwide effort to make battery recycling more affordable and energy efficient:

4. Is it true that it takes about 10 years for an EV to pay for itself? By that time, won’t advancements in technology make today’s vehicles obsolete? And what would that mean for people without home charging stations?

The short answer: It is true enough that it can take up to 10 years for an EV to pay for itself (i.e., to make up for its higher purchase price—relative to comparable non-electric models—via accrued savings). However, financing and making monthly payments, as 85 percent of new vehicle buyers do, can make EVs cheaper to own than gas-powered cars right off the lot. With vehicle, battery, and charger advancements sure to continue, it’s hard to say exactly what the EV landscape will look like in 10 years. A fair expectation, though, is that today’s tech will be slightly dated but no less operational.

Details: Many studies have shown that EVs have a lower total cost of ownership than gas-powered cars over their lifetime. This is achieved largely through fuel and maintenance savings over time. While there is broad agreement that it can take up to a decade to break even on an EV purchase, new research in the US finds that EVs are now cheaper to finance and own on a monthly basis than gas cars from day one. Factor in higher gas prices like the ones we’re seeing now, and those savings increase.

The technology will no doubt continue to evolve. That has its drawbacks, of course. But it’s also just the nature of technology. Considering the challenges we still face around the mass adoption of EVs, an evolution in the technology will ultimately be a good thing. It’s what’s needed to make better batteries, overcome today’s manufacturing and recycling obstacles, and make EVs more affordable and sustainable.

It’s also what’s needed to improve the efficiency and accessibility of chargers—advancements that are starting to pick up steam. While it’s true that today’s public charging infrastructure is still lacking, there are plans underway to beef it up in ways that will accommodate all current EV models.

Access to home chargers is a separate issue, but it’s one with potential solutions available right now. Even in an apartment or rental housing there are a range of at-home chargers currently on the market. In addition to home and public charging, workplace charging is an option for some, while wireless charging and battery swapping stations are among other concepts for the future.

There is also a solar-powered car set to roll out in limited quantities this year, starting at $26,000 and capable of providing 40 miles of range per day, which is plenty for people who are only commuting to and from work.

Looking ahead: We just did that! Still hesitant? Maybe the used EV market is the place for you.

5. Why aren’t we more focused on plug-in hybrids? They are fuel-efficient for the average middle-income person, and there isn’t a charge station requirement.

The short answer: It’s a great question. It’s a huge plus that they’re not limited to battery power exclusively. In practice, though, that flexibility tends to detract from hybrids’ actual fuel efficiency.

Details: In light of all the battery and charging conundrums that still need to be worked out—not to mention the domestic supply chain issues and frustrating tax credits for cars that don’t exist yet—why not dip our toes into EVs via plug-in hybrids first?

One reason, as Toyota’s chief scientist Gill Pratt told Axios, is that convincing people that hybrids are a good solution to ditching gas-powered cars is not easy to do, especially as governments offer incentives (at least in theory) to buy fully electric vehicles. Forecasters, including Boston Consulting Group, concur, predicting that EV sales will ”exceed all types of hybrid vehicles combined, and far outweigh those of internal combustion engines (ICEs), by the turn of the decade.”

Whatever the reasons, the road ahead looks more electric than hybrid. That may be for the best. When it comes to real-world usage, hybrids don’t equate to greater fuel efficiency or lower emissions.

“Most PHEV [plug-in hybrid] owners don’t plug in their cars,” according to Axios, “so they end up using gas anyway and missing the benefits of the partially electric life.” Still, “if you want to make an immediate impact on carbon emissions, plug-in hybrids aren’t a bad choice.”

Looking ahead: Hybrids are a reasonable middle-of-the-road option, even in some of the places where bans on gas-powered vehicles are in the works. In California, for example, where a ban on new gas cars was enacted for 2035, Inside Climate News writes that plug-in hybrids “may still be sold in 2035 and after, as long as they are capable of running at least 50 miles exclusively on battery power and as long as hybrids are less than 20 percent of an automaker’s new vehicles sold in the state.” As time marches on, though, it might be easier to find a place to charge than fill up.

I’m so excited about the solar Aptera! Great work. I’ve been driving my 2013 Volt for 8 years and just had a rebuilt battery installed (for free, thanks to California EV battery warranty 😊) and it shows no sign of dying, so – since the most sustainable thing for me to do is maintain my plug in EV, it might be a while until I buy another car. Maybe by then solar EVs will be abundantly available.