Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

Op-ed: The trust factor

With trust in the media and government near record lows, what can be done to repair some of the faith that has been lost?

Amid the cacophony of crises confronting us today, there is one that perhaps looms larger than most. One that, if left unaddressed, will make it difficult to tackle the many other challenges we face. This is the crisis of trust, the loss of faith in our most fundamental institutions, namely our media and government. Without it, our capacity to discern what is true and false is severely limited, and we are left questioning whether or not our leaders have our best interests at heart. As that trust erodes, so too does our ability to govern ourselves effectively, and to make the right decisions for our future.

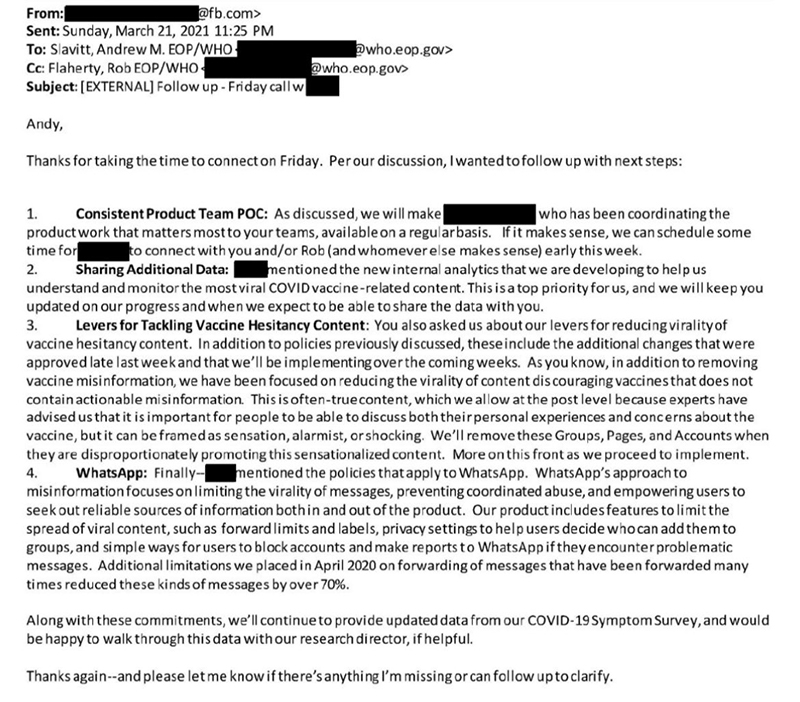

In forming our perceptions of reality, we rely on a multitude of sources—our own observations, information provided by those in our inner circle, the media we consume (including the vast expanse of social media), and so on. Yet, as we’ve discovered through recent revelations—via the “Twitter Files,” which in March were the subject of a series of House Judiciary subcommittee hearings—the collusion between government agencies and tech titans has resulted in concerns about censorship, undue influence over online content, the shaping of false narratives, and the withholding of information from the public.

The White House openly stated that it flagged “problematic posts for Facebook” to censor because they spread “disinformation”—posts containing things that, in some cases, later turned out to be accurate or at least possible. Even more alarming, leaked emails revealed that the White House also made requests to de-boost and remove posts that might increase vaccine hesitancy, including even correct information. Which raises the question: What else has been suppressed that we are not yet aware of, and what does this mean for our ability to trust media sources that are meant to provide us with the accurate information we need to form our views and inform our decisions?

It’s no wonder that, according to Gallup polls, Americans’ trust in media is near a record low, with only 34 percent of US adults having a “great deal” or “fair amount” of confidence as of 2022. While that decline is part of a decades-long trend, it still places Americans today with a lower trust in news than nearly any other country in the world. Trust in the judicial branch of government, meanwhile, sits at 47 percent, below the majority level for the first time in Gallup’s polling history.

Solving this problem will require a rethinking of how these institutions function and interact with people. It will also require greater honesty and transparency, and an acknowledgment of past mistakes. However difficult this task might be, it is necessary. Otherwise, we risk a future in which our society is torn apart by division and mistrust, our leaders are unable to lead, and our institutions are unable to function.

The question, then, is: How do we restore this trust? Do our institutions need to be dismantled, or can something more constructive be done to repair the faith that has been lost?

Restoring trust in media

While it’s not always the most practical answer, there may be something to the idea of building new institutions. After leaving The New York Times, journalist Bari Weiss turned to Substack to publish stories via her Common Sense media company, along with her popular podcast, Honestly. More recently, Weiss expanded her blossoming media empire by rebranding as The Free Press and building an in-house and independent news team to pursue investigative stories and commentary. The Free Press, as described on its website, is “built on the ideals that once were the bedrock of great journalism: honesty, doggedness, and fierce independence.”

Increasingly, independent journalism like Weiss’ and citizen journalism are emerging. The rise in the latter allows for voices to build reputations based on their ability to represent their local communities and likeminded followers, rather than on their status as journalists with elite credentials in far-removed newsrooms. It also means that those with niche subject matter expertise and storytelling talent can build platforms to disseminate information. This can prove invaluable compared to more generalized reporters who may lack specific knowledge and would have to rely on finding and evaluating “expert” sources for each story. And with the technical barriers of entry removed by way of platforms like Substack and YouTube, citizen journalists are now able to build their own followings more easily than ever.

When it comes to independent journalism, there has also been an immense growth of new outlets that are not beholden to mammoth corporate interests—including Weiss’ The Free Press and Ben Smith’s Semafor. Still, of the many new players on the scene, not all of the outlets that have emerged are necessarily the beacon of unbiased reporting and truth that some might be looking for. For starters, they have fewer resources for things like fact-checking and less human power to conduct on-the-ground research or spend substantial time on stories.

Also, many independent outlets started as non-neutral entities, as they were meant to go against the “mainstream” narrative and so are beholden to certain ideologies as well as audience capture. Their funding models are also often not clear. Many claim to be funded by readers, but that could also mean that a few deep-pocketed readers are providing substantial donations. Some seemingly independent publications (or journalists) have even been linked to special interest organizations—and even foreign government entities.

This is why, across the board—whether we’re looking at citizen journalists, traditional media, or independent outlets—there should be transparency about funding models and where the money is coming from. This is especially important when there are political ties or when editorial content is influenced by ad spends. (Early on in my journalism career, for example, I saw that an article I’d written for a major magazine had been edited to read as if the person I’d interviewed was endorsing a film, whereas he’d actually mocked it. A two-page ad for the movie’s DVD release followed several pages later.)

In 2022, the top 10 pharma advertisers alone had a combined spend of $1.68 billion in TV ads. Pharma companies had significantly bumped up their advertising spending at the start of the pandemic to promote vaccines and treatments, leading to concerns about the industry’s influence on media and potential conflicts of interest. Promoting vaccines was profitable business and many media outlets were accused of being too reliant on pharma advertising for their revenue stream to remain objective in their reporting. This skepticism was exacerbated by the spread of conspiracy theories and false information on social media platforms, as well as the politicization of the pandemic. Ultimately, this combination further fueled distrust and raised questions about the reliability of information sources.

Readers want to be allowed into the kitchen so they can see how the news gets made.

The key to both building and restoring trust is ultimately the same: Readers want to be allowed into the kitchen so they can see how the news gets made. Those who have lost trust are no longer satisfied with just being passive consumers and devouring whatever media diet they are fed.

Some ways to increase transparency: Show readers how stories are chosen and what the process of editing and fact-checking is like. (Are there any fact-checkers even remaining at newsrooms anymore?) Opinion pieces have their place, but they should be clearly separated from news stories and labeled as such. When a publication gets something wrong, instead of burying a correction at the bottom of the story, they should put it at the top. Better yet, they should keep track of corrections on their front page (or at least linked from it) and proudly announce how few they’ve had to make each month. If they’ve made an error in their tweet, it should be possible to update that tweet with a correction as well. The comment section should never be closed. It is what holds publications accountable to their readers and gives other readers a sense of what other people are actually thinking.

Taking it one step further, readers might be interested in publications that participate in a voluntary, opt-in certification program that rates a publication’s trustworthiness based on criteria like accuracy, quality of sources, transparency index ranking, and perhaps even readers’ publication-quality rating. (In a positive step towards increased transparency, the news comparison platform Ground News recently added some additional context about the media outlets included on its site, showing ownership, factuality, and media bias ratings.)

But readers need to take more responsibility, too. They should go out of their way to read publications that don’t simply confirm their existing beliefs. They should find writers who are committed to truth above ideology, and they should follow as well as support their reporting. They should be active readers who ask questions as they go along: What’s missing? Why is the person who is quoted in this article relevant to it? What are their beliefs and biases? Do they have an agenda? What else has the writer written? Can they be trusted to understand the topic? Where does this data come from? Does it check out? When a story gets something wrong, the reader should be proactive and reach out (politely) to the publication or author and alert them of this. It is up to us as a society to hold publications accountable, and to teach children (and adults) media literacy.

Economics is not a small factor in the decline in media trust, either. When people choose not to pay for high-quality content, which requires more time and resources to produce, the incentive to commission “clickbait” stories with quick turnaround times and greater audience reach becomes more appealing. As a reader, you have the power to challenge this incentive structure by refusing to cooperate with it. If you can financially support high-quality writing, do so. If you can’t afford to, share that writing with your friends and network, and avoid the temptation to engage with clickbait.

At the end of the day, there is room for new models, but it doesn’t mean that we need to tear down the old ones. We just need to improve them, and we can do so by learning from and correcting past mistakes.

Restoring trust in government

The same applies to government institutions. Perhaps nothing better illustrates how quickly government trust can be lost than the Covid-19 pandemic. Whether one agrees or disagrees with the government’s response, it is undeniable that the constantly changing guidelines and messaging stirred confusion. These policies triggered workplace lawsuits, brought up ethical concerns regarding travel and data privacy, disproportionately affected people who couldn’t work from home, and highlighted issues of digital censorship. All of this has contributed to a massive loss of trust.

But if we want to move toward building a more cohesive and functional society, then it is imperative that we work to restore at least some of that trust.

What can be done? To start with, an acknowledgement of responsibility and wrongdoing from leadership would go a long way. It would be especially effective if the departments and individuals responsible for making the policies specified what the wrong decisions were, apologized for them, and made amends. For example, a popular idea that has been floated around when it comes to people who lost their jobs due to vaccine mandates is to give those individuals a chance to return to their previous positions with back pay. In cases where those positions are no longer available, an alternate solution would be for the government to provide some sort of financial compensation for those job losses. Additionally, employees who were let go due to vaccine mandates could be prioritized over new applicants for any re-hiring done by their previous employers.

Too often, the willingness to admit errors—in other words, to take accountability—is seen as a sign of weakness. Many in power are too afraid to admit to past mistakes. But in truth, it is a key quality of a strong leader, and one that people can relate to. After all, who among us has not been wrong? When those in power take ownership of their mistakes and show their commitment to serving the people they represent, they take a step towards restoring trust. When they refuse to do that, they further erode public trust and sow the seeds of resentment and cynicism.

Transparency and limited government power are also critical. This starts at the election stage. Campaign budgets should be limited and uniform across all candidates to reduce the influence of money in politics and equalize opportunities for all candidates. Implementing ranked-choice voting would also allow voters the opportunity to express their preference for multiple candidates since they don’t have to worry about potentially “wasting” their vote on a candidate who might be less likely to win. This would allow us to break beyond our current duopoly, since switching to such a system would encourage more candidates who do not belong to one of the two major parties to run. It would also allow for more diversity to be expressed among voters, a record number of whom in the US now identify as politically independent.

As we’re seeing a growing trend towards decentralization—especially when it comes to digital currency—some recent discourse has shifted towards considering a more decentralized, smaller government. Some potential benefits of such a government are that it would have reduced bureaucracy and, at least in theory, increased responsiveness to local needs. It could also be subject to greater oversight by a third party—perhaps even a citizen body, not unlike how election scrutinizers operate during a ballot count.

In Norway, for example, the Office of the Auditor General is an independent agency that audits the government’s financial statements and evaluates how effective its programs are, reporting its findings to both the Norwegian parliament and to the public. In New Zealand, the Office of the Ombudsman operates independently to investigate complaints about government agencies, which again, are made public. All of these initiatives help keep the respective governments more transparent and accountable to their citizens.

Governments also need to do a better job of letting voters and taxpayers know—in detail—what it is that they are doing with their money and their resources. Employers expect employees to provide Key Performance Indicators (KPIs) and report on their achievements, so why is it that we demand less of our appointed leaders?

We’ve seen a lack of transparency and accountability in numerous decision-making processes. These include the Iraq War and weapons of mass destruction, which were based on faulty intelligence; revelations in 2013 about the National Security Agency’s (NSA) surveillance programs on its own citizens; data collection and reporting by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Health and Human Services (HHS) during the pandemic; the poor and hasty evacuation of US citizens and allies from Afghanistan; the handling of the SolarWinds hack by the government’s cyber defense, as well as its poor communication with the public, in 2020; and many other examples. All of these undermine the public’s trust. And while it is understandable that some activities do need to remain secret in the name of national security, there are many instances where this is not the case, and where making data more accessible to the public would have helped to earn its trust.

Broadly speaking, people want more say over what they get from their government, and perhaps it’s a radical idea, but why not let taxpayers choose on their tax forms where some of their money will be allocated? What if they could check a box that says that X percent of their taxes will go towards policing, healthcare, education, the environment, and so on, so that, in essence, every tax year there was a practical referendum using people’s actual tax dollars? They might begin to feel like they have an actual say about what happens with their money.

As things stand now, there’s too much that goes on behind closed doors. Massive lobbying groups have plagued Washington for years. Private interests pay for time with politicians. Politicians go into the office to serve but somehow come out on top with millions of dollars. How does that happen? Reforms are needed to address these issues. These could include bills to introduce measures like limiting campaign donations, barring PACs, not allowing individual or corporate donations over a certain amount, and forbidden exchanges of money (or in-kind services) for time with politicians serving in office.

To address the specific issue of politicians making millions off their time in office, strengthening conflict of interest laws is key. This could include creating an independent citizen-based ethics commission to investigate complaints of misconduct, and increasing penalties for unethical behavior.

A variety of views and voices should be the aspiration.

While we’re at it, there have been so many bills that would have bipartisan support and yet repeatedly get stuck on the floor. Why? Because they get bundled with other bills that are far less palatable for the opposition. This makes it appear as though the policies—like abolishing “no-knock warrants,” for example—have less support from the parties than they actually do. Exploiting this, opposing parties make a game out of pretending that some really common-sense bills get rejected when, in fact, it’s not those bills that the other party opposes, but rather the ones that they are bundled with. This in turn feeds the sense some have that their government is ineffective, incompetent, and can’t be counted on to get things done. So perhaps it’s time to do away with the bundling of bills. Each bill should be considered on its own merits—unless there’s consensus from opposition—so that lawmakers aren’t forced to vote for provisions they disagree with. Bills should also be posted online for a certain period of time before being voted on, with committee hearings made public—and allowing for comment from the public as well, so that citizens can take a more active role in shaping the policies that affect them.

In addition, a variety of views and voices should be the aspiration. Instead of censoring voices or promoting a homogeneity of opinions, government institutions should implement an approach that ensures that a wider assortment of backgrounds and opinions is included, particularly within fields like technology, science, medicine, education, and other relevant disciplines. Civil disagreement should be encouraged, not reduced, and government grants should not be dependent on consensus between a group of scientists, for example.

There is vast agreement on climate science, but there are highly qualified dissenting voices—should their research not receive funding? What if on some points that others aren’t looking into, they turn out to be correct? History is filled with such examples. Australian physician Barry Marshall and pathologist Robin Warren were awarded the Nobel Prize in Medicine in 2005, but had struggled for years to secure funding for research and were dismissed by many in the medical community for their theory that stomach ulcers were caused by the bacterium Helicobacter pylori. Similarly, in the 1960s, biologist Rachel Carson was ridiculed and attacked for her concerns over the dangers of pesticides and their impact on the environment. Today we accept her warnings as fact. This is why it’s so important to explore scientific ideas even if they go against popular consensus.

But perhaps most important, in order to earn the public’s trust, government institutions also need to be able to trust the people themselves. They need to show that trust not only by being transparent and accountable to the people that they represent, but also by not taking it upon themselves to be the arbiter of deciding what is for the “greater good” of others, particularly when those decisions go against majority public opinion. That means that they should empower people to make choices for themselves by providing access to as much information as possible, but never depriving them of that information or those choices.

I think you are not really understanding the scope of lies society faces. Leaders won’t apologise as they are not sure they are wrong and refuse to look. Much of the institutional infrastructure would work, if folk were competent and honest. This is the crux of a hearts and minds social and economic warfare. Powerful interests know the tools and expect to use government assets to defend personal interests; governments are presented these “corporate goals” as support for the economy. In truth no country should allow such budgets for intelligence – we are literally paying to be stupid in the future in order to hide objectives. Secrecy is another aspect no sane civilisation has forbidden secrets and the cults of religion only talk about secrets – the US government has secrets that require new levels of encryption.

From my perspective it is obvious our governments have given up. I was an investment accountant looking at global markets and global risks. The models and analysis used to be very strong – effectively the probability for any outcome can be calculated. Understanding our ability, you understand there is an intention to be incompetent embedded in the leadership process. Decision making and responsibility split in such a way that the leader has “plausible deniability” in the scenario where all options are plausible – leaders can take the largest bung..

It is the concept of limited liability in law that is destroying society. The idea that ignorance equals forgiveness. Corporate lawyers embed ignorance into every decision so profit can be maximised. Greater good issues often left undefined in law to promote best practice are unrecognised in corporate decision making as there is very low probability of enough individuals gathering together and fighting through the big book of plausible reasons why acting against the common good occurred, is measurably slim. It is the idea of god or karma or justice will occur even if there is no route for it; in reality the law allows powerful interests to do anything they want. The law is the glue of society, we all agree to it as a way to live in harmony. Legislative powers are now routinely abused to create corporate advantages and just because the gender issue seems a bit on the edge folk don’t care. I picked the gender issues on purpose because looking at terms to describe human life and qualities of life has a totally different context from the perspective of AI, genetic engineering, cloning and so on. When everyone in society works for money; you really must ask who is paying for these narrative tunes and what result are they aiming at.

To counter religious belief nonsense we actually need to promote reason and logic. I expect a few beliefs won’t hurt provided they don’t effect your ability to be reasonable. The world needs to act on facts now. Climate issues have always been subject to information warfare – weather war was a wet dream of the allys in the second world war. Anyway my assessment of the data is it is past time to do something – it is an impossible idea that our governments and businesses don’t realise this but facts are obscured. From looking at these factors on a global scale population means that any food or resource shortage can easily result in billions of deaths. If we approach such times loaded for war, I see the death toll rise and the planetary issues become primal. Folk don’t realise the baked in element of climate mean its about the survival of earth – leaders are so scared they are doing exactly what existing powers tell them and acting daft when it comes to the plight of the majority. The critical factors not observed in the debate: Oxygen and natural diversity. The other side of CO2 with nearly 10 billion humans and supporting animals burning rockets and tanks just might not cycle the oxygen back in time no trees you see. If temperature changes inhibits monoculture well expect grave damage to those areas of earth where the air gets thin.

I am planning just to fix this and ignore the stupid, when I work out how to do it I will tell everyone. Good luck in fixing things, remember powerful folk like it broken.

Love peace, Rob

Yes, yes, and yes! I love your vision completely. The one thing I want to add is for term limits for the house and Senate. The longer they are there, even the MOST honorable of people keep seeing their colleagues get large sums of money for their campaigns, while they struggle to raise funds. Or watch them become millionaires on a salary of $174k/year. The longer they are there, the more “game playing” goes on and scores need to be settled rather than the people’s business being done. They came into office to do good. Politics, time, and money corrupt them, even if they are using corrupt methods to do the good they came to do! 2, four year terms in the House, and 2, six year terms in the Senate.

As far as government agencies, some will have to be completely overhauled. When J. Edgar Hoover was made “FBI director FOR LIFE” because he had the goods on FDR, did we think the corruption would end once he died? They still try to control Washington by surveillance of politicians, blackmail and then tell them how they will vote, etc. Then the system DOES end up in the hands of some powerful people, instead of in the hands of the people.

Finally, the big answer to all of this is still in the citizen’s hands. We MUST be engaged in our government. We MUST hold them accountable. The only reason this has gone on for so long is the malaise of the people. Also, the government NOW has us fighting each other, and letting them do whatever they want. What do they want? Absolute power. That comes from years of grinding down every last bit of integrity in them, both sides. While a small number of powerful people call the shots. If we can all rally together and take our country back through the will of the people and put aside petty differences, we will have what we were promised “Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness”.