Volcanoes are erupting in The Philippines, but on-fire Australia received some welcome rain. The Iran war cries have been called off and The Donald’s military powers are about to be hamstrung by the Senate. Meanwhile, his impeachment trial is starting, and we’re all on Twitter for a front-row seat.

Americans deserve a better political system

Ideas for increasing civic pluralism, rebooting institutional independence, and building a better media

As a sobering new report from the Pew Research Center highlights, Americans are over politics. When asked how they feel when thinking about politics these days, nearly two-thirds of Americans say they always or often feel “exhausted” by politics, and another 55 percent say politics makes them feel “angry.” A scant ten percent of Americans feel “hopeful” when thinking about politics, and less than five percent say they get “excited” thinking about politics. Asked to describe their views of politics in their own words, only two percent of respondents had anything positive to say, and the dominant words were “divisive” and “corrupt.”

Sadly, only four percent of Americans believe the political system is working extremely or very well, and 63 percent express little or no confidence in the future of the political system. Pew also reports that majorities of Americans view both parties unfavorably, and nearly three in ten Americans now hold unfavorable views of both political parties—the largest percentage in three decades of tracking on this measure. Consequently, nearly seven in ten Americans say they “often wish there were more political parties to choose from” in our system.

Political analysts often examine the issues of polarization and rising partisan animosity as driving forces of the contemporary scene. These are serious issues for certain, as more than 60 percent of Republicans and more than half of Democrats in 2022 expressed very unfavorable views of the other party—compared to only around one-fifth of both sides who felt this way in 1994. Politics has gotten meaner and more divided, particularly between members of the two opposing parties.

But as the Pew data shows, the bigger trend influencing American democracy is that people are just fed up with politics altogether—they don’t want to hear any more lies and nonsense from political leaders and parties and the media operations that pump partisan vitriol 24-7.

So, what can be done about it? Action is needed in three areas: (1) increasing civic pluralism and tolerance among citizens; (2) promoting more independence among the institutions of civil society; and (3) building better, more neutral, fact-based media operations to counter the forces of partisan polarization.

Here are some ideas for making progress in each of these areas as laid out recently in my publication The Liberal Patriot:

Embrace more nonpolitical aspects to life. People mostly get along just fine outside of the world of partisan politics and the media scaffolding that supports it—think about the workplace, neighborhood or school gatherings, sports teams, book clubs, the military, or various interfaith groups. These nonpolitical organizations work well precisely because they encourage cooperation between people with multiple backgrounds and perspectives. In general, everyone agrees to do things together—or work toward a common goal—rather than always pressing their own interests and personal identities.

The more people engage in these pluralistic organizations, and the less they engage in combative partisan politics, the better.

Keep politics out of most relationships and institutions. When people violate pluralistic norms in the workplace or at school or in some other organization, things start to fall apart. This is increasingly the case today as formerly nonpolitical institutions have now been overtaken by people pressing the same dumb culture wars and partisan politics that drive people mad and create conflicts elsewhere.

Don’t be this person. We all need to do a better job of keeping our politics separate from the rest of life—and people in positions of authority within institutions need to better enforce pluralistic norms and rules to help keep it that way.

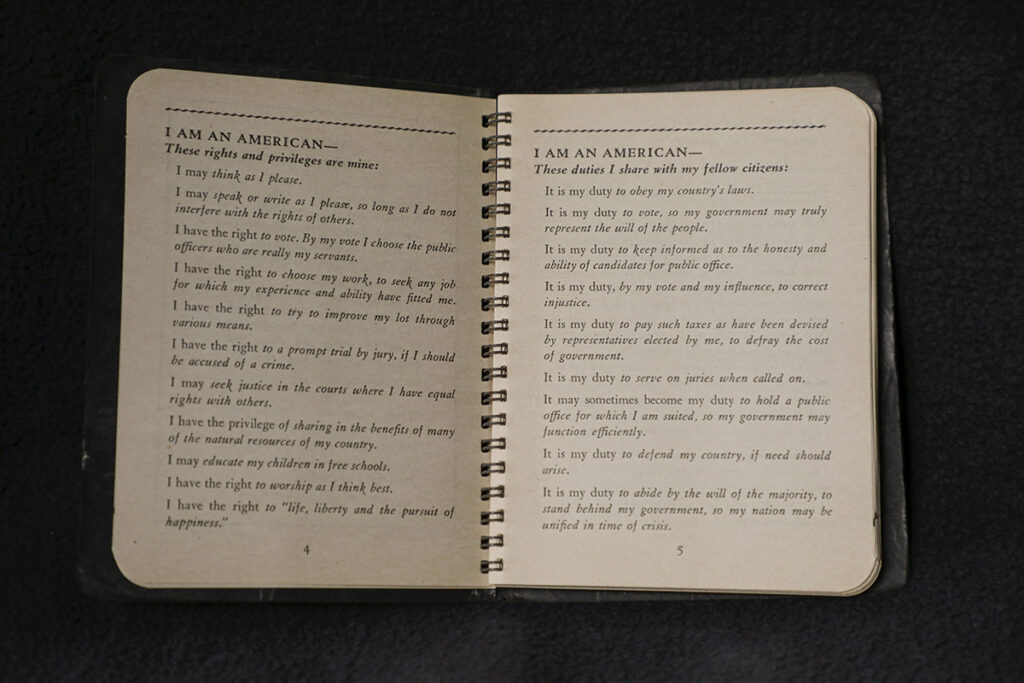

Resist social pressures to conform to narrow partisan beliefs and negative opinions of others with different views. Partisan politics today is little more than two petty and stupid high school cliques demanding conformity from people inside the group and demanding hatred of those outside of the group. Who cares really? It’s fine for people to vote for Republicans or Democrats—or to vote for some other party or not to vote at all. We still have to find ways to tackle common economic and security challenges across party and ideological lines to be successful as a nation.

No single party will ever fully dominate the other, nor should it. Just vote for whomever you want to vote and support whichever ideological faction you want. But remember: no one else is your enemy for supporting different political ideas, leaders, or parties.

Try harder to understand the positions of those with different backgrounds and opinions. This is understandably difficult because it requires patience and listening, empathy, and open-mindedness—values in short supply in today’s partisan landscape. But to truly uphold a principle of “live and let live” with mutual respect, people at least need to try to see things from another’s perspective—based on their own terms and understanding rather than a biased conception of those views.

This doesn’t mean acquiescing to values and ideas that might be alien or abhorrent; it merely means respecting other people’s right to see things in a different way as part of living peacefully and cooperatively in a pluralistic democracy.

The single best antidote to ideological and partisan conformity within politics is a true blossoming of divergent ideas and groups across civil society.

Reboot American civil society. The single best antidote to ideological and partisan conformity within politics is a true blossoming of divergent ideas and groups across civil society. The philanthropic world is currently arguing over how best to encourage value pluralism in America—that is, how people with different viewpoints and value systems can listen to and learn from one another and figure out how best to get along within our democracy. At the same time, ideological and partisan conformity have taken over many institutions that were once dedicated to different philosophical approaches, the pursuit of individual group interests, or more neutral and analytical policy research and development.

The networks of astroturfed “grassroots” organizations, think tanks, and other giant campaign organizations on both the left and the right today no longer function as independent bodies developing new ideas, gathering and analyzing neutral facts, brokering compromises, and supporting mutually beneficial, big-tent politics. Rather, the institutions that make up these political networks often converge on the same set of ideas and positions within a commonly accepted and enforced partisan framework that serves the interests of those currently in power—or those seeking power.

Dissident ideas are pushed to the side. Competing or uncertain evidence about what works in public policy is mostly ignored, as so-called independent institutions churn out propaganda to bolster the issue positions of specific political parties or leaders. This is a relatively new phenomenon. After the Supreme Court eliminated most restrictions on campaign financing, leading “nonpartisan” organizations on the left and right dispensed with the fiction that they are neutral research institutions merely going where the evidence takes them. Instead, using unlimited and often untraceable private dollars, these groups aligned their work intellectually and politically with respective partisan interests to advance whatever positions are most important or pressing at any time.

Instead of investing in a competition of ideas within and across political movements, as pluralism requires, most civil society work in contemporary politics amounts to little more than advocacy in support of the two parties.

What is desperately needed from philanthropists and citizens themselves is a serious recommitment to independent research and genuine grassroots or interest-based organizing that seeks concrete objectives across partisan and ideological lines. Rather than plop another billion dollars into fake political activism that encourages partisan standoffs and over-the-top ideological rhetoric, philanthropists should spend more of their money on groups and institutions that encourage diversity of thought, look for compromises among competing segments of society, and value political tolerance on a wider scale.

Restore a genuine commitment to viewpoint diversity and free expression. Ideology and politics have invaded nearly every aspect of contemporary life from the workplace to schools to religious and secular organizations. On the left, a stated commitment to “diversity” in major institutions includes every demographic group under the sun with no concomitant desire to include people with different moral or political views. On the right, stated opposition to these leftist initiatives and a supposed commitment to “free speech” has morphed into yet another set of ideological dogmas about what people can or can’t say, read, do, or think.

Neither the left nor the right—and the moneyed interests fueling each side—cares one lick about including people with different perspectives or listening to those with divergent views. Activists on both sides enforce this institutional conformity by punishing and shunning those who stray from the party lines.

More institutions need to follow the lead of the University of Chicago with its statement of principles supporting free speech and diversity of thought. Other non-academic institutions in civil society would benefit greatly from a similar commitment to free expression and the unimpeded exploration of ideas within a framework of mutual respect, tolerance, and equality for all.

Break up the two-party duopoly to support a range of parties and ideas. The Atlantic recently ran an interesting piece on the different ideas within the political science and democratic reform communities to help loosen the iron grip of the two political parties on the American system. Without going into elaborate detail on each proposal, the one that makes the most sense in terms of Madisonian pluralism—a proliferation of competing factions and interests working within a democratic structure—is the idea of proportional representation in national, state, and local governments.

The idea is simple (if difficult to pass legislatively given current politics): eliminate winner-take-all systems that lead to one-party dominance and instead set up larger political boundaries with multi-member representation based on the percentage of votes for any given party. Instead of states, cities, or congressional districts being controlled entirely by one party or the other—locking out all minority viewpoints—political competition would be restored and additional parties would have a real shot at representation based on the percentage vote for each party.

Create more neutral commercial media platforms. A wealthy person or investor group somewhere can certainly figure out how to create top-notch journalism and social media platforms that are interesting to consume and use, while also being neutral and more analytically focused on substantive concerns facing the country. Editorially, these new ventures should reduce partisan politics and elections to one quarter of coverage, and dedicate the other three quarters to reasoned examinations of issues, consideration of a range of empirical evidence, critical analysis, and compelling personal stories about economic and social problems facing the nation—and possible solutions to them.

Flip the script on political media and give the disaffected masses what they want: measured, independent, nonpartisan news and analysis. Surely some enterprising business minds can determine how best to make money doing the right thing for American democracy.

Fund more nonprofit media. Much of what really affects American life occurs at the local level—the actions (or inaction) taken by municipal and state governments, local businesses, and organizations. Yet the demise of high-quality community journalism has eliminated nearly all coverage of these local developments, and opened the door for regular partisan screeds and cultural fights from national outlets to flood the zone. Philanthropists could do much more to seed high-quality nonprofit journalism at the local level, like The Baltimore Banner, to provide rich coverage of city governments, local neighborhoods, and regional businesses and cultural offerings.

Like The Banner, fully digital operations can be less expensive than other media ventures to set up and maintain and can be augmented by small donations and subscriber fees.

Greatly expand America’s public media options. PBS and NPR, plus Voice of America and Radio Free Europe, are excellent public media outlets offering more substantive coverage of national and world affairs—and most importantly, are widely available and mostly free to Americans and others around the world. But we could raise our national ambitions to match those of the BBC—a full-scale, professionalized operation with branches across the country and globe with a mission “to act in the public interest, serving all audiences through the provision of impartial, high-quality and distinctive output and services which inform, educate and entertain.”

Americans would gladly pitch in some of their tax dollars for the development of first-rate, neutral, substantive coverage of national and global issues and interesting cultural and personal stories. Public media must be independent to be effective. But given the reality of politics, a group of bipartisan members of Congress could get together to create a mutually accepted framework for oversight of this expanded public media operation.

The verdict on contemporary politics and media is clear: Americans don’t like the current state and trajectory of our political system. We can keep stumbling along hoping that partisan polarization and overheated politics will somehow subside, or we can take steps as citizens to improve the situation and begin rebuilding trust in collective action and government.

James Madison and the other founders would certainly approve of some pluralist experimentation to uphold individual rights and the common good—so let’s give it a shot.

The ideas in this article are adapted from John Halpin’s The Liberal Patriot, an online newsletter focused on US politics and policy and international affairs.